Why $650 Billion in AI Spending ISN'T Enough. The 4 Skills that Survive and What This Means for You.

Now Playing

Why $650 Billion in AI Spending ISN'T Enough. The 4 Skills that Survive and What This Means for You.

Transcript

620 segments

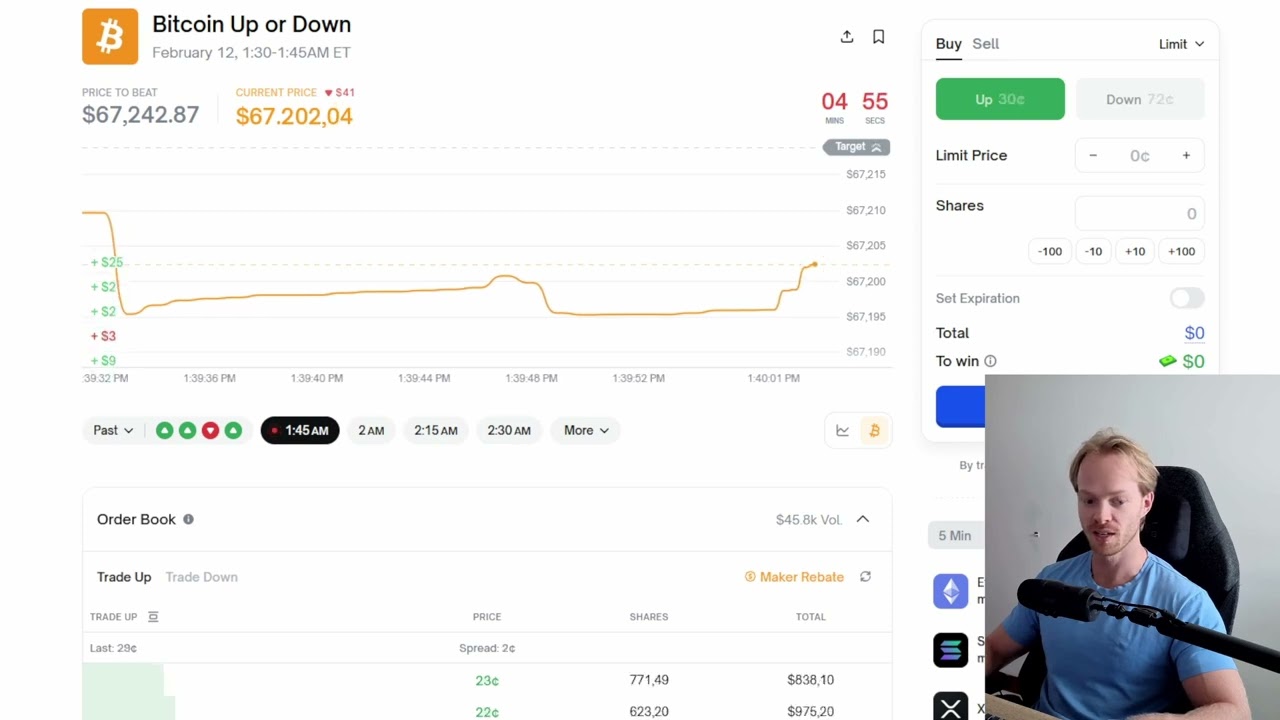

Google is spending $185 billion on AI

and it's still not enough. They just

told investors that's how much they're

spending on AI Infra, and the stock

dropped 7%. Not because Wall Street

thinks the number is too high this time.

It's because Wall Street is starting to

realize it might not be high enough. So,

Alphabet reported Q4 earnings on

February 4th, the same week a markdown

file erased $295 billion in enterprise

software market cap. The earnings

themselves, they were immaculate from

Wall Street's perspective. Revenue

exceeded $400 billion for the first time

in company history. Earnings per share

crushed it. Cloud revenue accelerated.

If you're an investor, it's everything

you want to see, right? By every

conventional measure, the company seemed

to be performing at the peak of its

powers. And then Sundar Pitchi announced

the capex number. Somewhere between 175

and $185 billion in one year in 2026.

That's roughly double the $91 billion

Google spent in 2025, which itself was a

74% increase over 2024. Analysts had

been expecting around $120 billion.

Google blew past that expectation by

50%. CFO Anat Ashkenazi broke down the

allocation. About 60% of that money pile

is going to servers and 40% is going on

data centers and networking equipment.

Sundar described maintaining a quote

brutal pace to compete on AI. I think

that word choice was very deliberate.

This is not a company making necessarily

a measured strategic investment,

although they'll probably portray it

that way. This is a company sprinting

because it believes the cost of slowing

down is existential. Now, you know, the

stock recovered most of its after hours

losses by next day's close. This is not

about the stock per se, but the initial

7% drop should tell you what the

market's instinct was before the

analysts had time to write notes.

185 billion sounds like too much money.

It sounds reckless. It sounds like a

company that has lost discipline and the

market's instinct is wrong. And the

speed at which it's becoming obviously

wrong. That's the real story. You know,

6 months ago, this was all a bubble. Do

you remember that? If you rewind to mid

2025, the dominant narrative in

financial media was that AI

infrastructure spending had just

decoupled from reality. Oldman Socks

published a widely cited research note

asking whether big tech was spending too

much on AI with too little to show for

it. Sequoia's David Khan wrote his $600

billion question analysis pointing that

pointing out that the total revenue of

all AI companies combined could not

justify the infrastructure being built.

Jim Cavell at Goldman called generative

AI overhyped. The list goes on and on.

This was the consensus. This was built

on real numbers. Training runs cost

hundreds of millions of dollars. Then

agents happened. Not the concept of

agents. People have been talking about

AI agents of course for years, but the

actual deployment of agents into

production workflows, consuming

absolutely massive amounts of inference

tokens and delivering value that was so

obvious the market has started to wake

up and can't ignore it anymore.

Anthropics Claude Co-work shipped

plugins that can triage legal contracts,

that can automate compliance reviews,

that can generate audit summaries. That

legal plugin is just 200 lines of

structured markdown and it wiped 16% off

Thompson Reuters. Open AAI is in the

game, too. They launched Frontier, an

enterprise agent platform, and signed up

HP, Intuit, Oracle, State Farm, and

Uber, all as launch customers, not for

demos, but for production deployment.

Coding agents at Cursor, Codeex, and

Cloud Code have crossed from useful

autocomplete, which was the joke at the

beginning of last year, to autonomously

generating thousands of production

commits in a single year. The agents

didn't just work. They consumed compute

at a scale nobody has modeled before.

Every agent running a contract review is

making dozens of inference calls. Every

coding agent generating a thousand

commits an hour, a real number, by the

way, is burning tokens continuously

around the clock at a rate that makes

chatbot usage look like a rounding

error. When you multiply that by

enterprisecale deployment across legal,

finance, engineering, compliance, the

inference demand curve just goes

straight up. It goes vertical. And just

like that, the narrative of the bubble

has flipped. Not gradually in weeks. The

question has stopped being, is AI

overhyped? It has started being, do we

have enough compute for what's about to

happen? $285 billion SAS apocalypse

wasn't just a repricing of software

companies. It was the market absorbing

in real time that AI agents are powerful

enough to restructure entire industries

and that the infrastructure to run those

agents at scale does not exist yet.

Derek Thompson captured the shift with

precision. The odds that AI is a bubble

declined significantly and the odds that

were quite underbuilt went up. He's

right. You cannot simultaneously believe

that AI agents are powerful enough to

crash enterprise software and also that

the infrastructure spending to support

those agents is excessive. You got to

pick one. I need you to understand how

big the scale of the bet is to

understand how wild it is that we might

be underbuilt. Google's not alone in

that giant capex spent. That's the first

thing to understand on spending even

more. They announced roughly $200

billion in 2026 capex. Microsoft is

running at about 145 billion annualized

metaguided to between 115 and 135

billion driven by its super intelligence

labs buildout. Even Oracle, which barely

registered in cloud infra a couple of

years ago, is deploying tens of

billions. Add it all up, the five

largest tech companies on Earth, are

going to spend somewhere close to $700

billion in one year on AI

infrastructure. Goldman is projecting

that's going to rise to well over a

trillion between 2025 and 2027. That's

probably conservative. These are numbers

that do not fit neatly into existing

frameworks for evaluating corporate

investment. And I think that's why

market reactions have been so wild.

Microsoft's capital intensity has

reached 45% of its revenue. Historically

absolutely unthinkable for a software

company. Amazon's capex has already

exceeded its total annual free cash flow

and forced them to tap the debt markets.

Google is about to spend more on

infrastructure in a single year than the

entire GDP of Ukraine. The natural

reaction is that this has to be a

bubble. That's what people assumed. And

for 6 months, that reaction was very

defensible on Wall Street. It isn't

anymore. And look, I'm not saying the

bare case was stupid. I'm just saying it

aged out. OpenAI's annual recurring

revenue hit 20 billion dollars in 2025.

Impressive, but that's the largest AI

company in the world, and its revenue

represents roughly 3% of the

infrastructure investment being made on

its behalf. The math doesn't come close,

which is what the bears have been

saying. Not this year, not next year.

Every previous infrastructure boom has

looked like this, spending wildly ahead

of revenue. And everyone has assumed

that's going to end in tears like it's

ended in tears before. But the

conclusion the bears drew died this

week. The SAS apocalypse is a proof of

demand. Not projected demand, not

theoretical demand, but revealed demand

priced by the market in real time. If if

AI agents generate $285 billion of

software cell conviction, we are

restructuring how enterprise economics

work in real time. And it's around AI

agents. And it's not just about market

reactions. Enthropic went from fewer

than a thousand business customers two

years ago to over 300,000 by September

of 2025, many more now, and they reached

44% enterprise penetration by January

2026. Open AAI's revenue has tripled.

Frier Sarah Frier, their CFO, says

enterprise now represents roughly 40% of

the business. And it's no coincidence

that the day after Google's capex

announcement, OpenAI launched Frontier,

an enterprise agent platform, and signed

up that list of who's who in the

enterprise business like Uber, like

Oracle as launch customers. The Bears

were making the right argument 6 months

too late. There just isn't space in the

world right now for bears that can't

recognize that token burn is going to go

up by a thousandfold. You know, every

major economic era begins this way.

Massive overbuilding of infrastructure,

investor panic, the infrastructure looks

like a catastrophic mass allocation of

capital. And then a few years later,

somebody figures out what the

infrastructure is actually for. The

railroads did this first, right? The

American railroad mileage doubled in

just 8 years between 1865 and 1873. And

that looked like way too much way too

fast. and five years of depression

followed because 121 railroads went into

bankruptcy and took out 18,000

businesses. But then a guy named Philip

Armor figured out refrigerated railroad

cars and suddenly you could ship fresh

meat from Chicago to New York and then

to small towns everywhere and suddenly

you had an application for railroads.

Fiber optics repeated that same pattern

a century later. Between 1996 and 2001,

telecoms issued over $500 billion in

bonds and laid 90 million miles of

cable. And then the bubble burst and the

wreckage was staggering. A trillion

dollars in debt were written off. 95% of

installed fiber went dark. And then

YouTube launched on bandwidth that cost

almost nothing. And then Netflix pivoted

from DVDs to streaming. The economy that

they enabled became the largest in human

history. the economy that they enabled,

the streaming, the cloud, the entire

modern internet, that became the largest

in human history. And it was all

underpinned by the commitment to fiber

in the 1990s. So that's been the

pattern, right? Massive investment,

crash, and discovery. But this cycle has

a structural difference that changes the

math and nobody's talking about it.

Railroads were dumb pipes. Fiber was a

dumb pipe. AI infrastructure is not a

dumb pipe. Google, Anthropic, OpenAI,

they're not really selling bandwidth.

They're not selling storage. They're

selling intelligence. Every inference

call is a purchase of cognitive

capability. The model is the product and

the infrastructure exists to serve the

model at scale. When an agent reviews a

contract or writes code or manages a

supply chain, the value it delivers

flows through the model provider's API.

The infrastructure and the intelligence

are vertically integrated in a way that

railroads and fiber never were. And this

means that companies building AI

infrastructure are positioned to capture

value from the applications built over

the top. Not just hosting fees, but an

actual share of the cognitive work those

applications perform. That is a very

different economic structure than any

previous infrastructure buildout. It

doesn't guarantee that any of these

companies are going to win, of course,

but it does mean the analogy to telecom

companies going bankrupt is kind of

misleading. The model makers are not

laying dumb cable. They're selling the

thing that makes all of our computers

valuable. Now, there's also an important

distinction in the AI infrastructure

conversation that most Wall Street

observers have been missing, and it's

the key to understanding why the bubble

to underbuilt narrative has flipped so

quickly. The first wave of AI infra

spending from 2023 out to mid 2025 was

primarily about training. Build those

massive clusters of GPUs. Train

foundation models. Training is

expensive, but it's also bursty, right?

You need a lot of compute for months and

then the model's done. The investment is

very front-loaded. This is the phase a

lot of the bears were analyzing when

they called it a bubble. But the phase

we just entered is about inference. It's

about running those trained models at

scale continuously for millions of users

and frankly millions of AI agents 24

hours a day. Now, inference is cheaper

per unit, but it never ever stops.

Agents change the inference math in a

way that nobody really priced in outside

of a few folks who were optimistic in

San Francisco. A human using Chat GPT,

they'll generate a modest inference

workload. an agent is going to generate

a thousandx a human workload if they're

reviewing contracts, if they're writing

code. You there's no way that you can

get anywhere close to par with a human

if you're an agent because of the pace

at which an agent executes. Now multiply

that thousandx gain by every workflow

the SAS apocalypse said was about to get

automated. Think about contract review.

Think about financial auditing. Think

about data analysis. Think about CRM

management and customer service. the

enterprises signing up for OpenAI's

Frontier for Cloud Co-work, they're not

thinking about it as we're deploying one

agent. They're deploying fleets of

agents. And that's why the narrative has

flipped so violently. Wall Street has

finally figured out that $650 billion or

$750 billion, whatever the number is

going to be this year, that's only

insane if you're building clusters for

chat bots and you're just training new

models. That's not how it works right

now. We are serving models for agents.

It's an entirely different world. And

the 6040 split that Google's CFO talked

about, Google understands this. They're

not building training clusters anymore.

They're building inference capacity for

a world where AI agents are the primary

consumers of compute. You don't build

60% servers and 40% data centers if

you're not in the inference business.

And even that framing understates how

big the gap is right now. Fijiimo,

OpenAI's CEO of applications, said

something this week that most people

glossed over. She said, "We spent months

integrating and we didn't even get what

we wanted. The CEO of applications at

the most valuable AI company in the

world said enterprise AI integration is

harder than expected. Not because the

models aren't great, but because the

infrastructure to connect AI agents to

enterprise systems is not mature enough.

The plumbing is not there where it needs

to be. The connectors aren't there where

they need to be. the security layers

aren't there where they need to be.

Demand is exploding, but it's way out

running the plumbing. And the plumbing

is what that 650 to700 billion is trying

to close. You know, every infrastructure

inversion has a window usually I don't

know half a dozen years, 3 to seven

years, call it, where the infrastructure

is being built and the companies that

will eventually use it are just getting

started. The companies that build during

that window end up becoming the

platforms and the companies that wait

become the tenants. Amazon built AWS

between 03 and ' 06 and had the dominant

cloud platform before most enterprises

even knew they needed one. The companies

that waited for cloud to prove itself

ended up paying Amazon's margins for the

next 20 years. That window is open now

on AI infrastructure, but the timeline

is compressed in a way that should

concern anyone who thinks they can wait.

Look, railroads took something like two

decades to overbuild before the economy

justified them. Fiber took a decade. AWS

took six. It's compressing. The current

cycle is moving at roughly 18 months

because the demand signal does not take

years to arrive. It arrives fast because

agents are developing that fast.

Google's $185 billion spend. It makes

sense when you understand that

compression. They're not spending too

much. They're spending at the pace

required to build the platform layer

before somebody else does. The same is

true for Amazon, for Microsoft, for

Meta. None of them can afford to wait

because the lesson of every prior

infrastructure inversion is that the

platform builders capture the economics

of everything built on the top. If you

miss that window, you're renting someone

else's infrastructure for the next

decade. The companies that look like

they're burning cash in 2026, the big

five, will look like they were laying

the foundation when we look back at

2028. And the companies that showed

quote discipline by spending less are

going to end up missing the most

important infrastructure buildout since

cloud. So where does this infrastructure

actually go? Who gets to run on it? The

answer requires taking the current

trajectory really seriously. And most of

us are not doing that because that

trajectory is profoundly uncomfortable

to our brains. Code proved to be the

breakthrough application for agents. And

the reason is worth understanding

because it tells you where we're headed.

Code is the one domain where an agent's

output is immediately and objectively

verifiable. You run it and it works or

it doesn't. That feedback loop is the

kind of iterative cycle that agents

excel at. There's no ambiguity, no

subjectivity. It works or it doesn't.

And that's why coding agents crossed

from useful to transformative so

quickly. Now, today coding agents work

in bursts. An hour here, a few hours

there, guided and directed by humans.

But the trajectory is really clear.

Context windows are expanding. Working

memory is multiplying. The ability of an

agent to hold a code base in its head is

expanding every few weeks, not years,

weeks. Opus 4.6 5x working memory versus

4.5 in just the space of a couple of

months. If that pace holds and there's

zero evidence it is decelerating, then

by the end of the year, we're looking at

agents that can do months of work. Think

about what that means for infrastructure

demand. in agent coding autonomously for

a month continuously generating and

testing and refining is consuming

inference compute at a volume that no

analyst model has properly accounted

for. We're just not good at exponentials

as humans and code is just the domain

where the feedback loop closed first.

Legal analysis is next. Contract review

has really clear success criteria.

Financial auditing is similar. Medical

diagnostics is similar. Engineering

design is similar. Domains where output

quality can be systematically evaluated

are domains where agents can cross from

useful to autonomous faster than people

are planning for. The infrastructure

that looks like an overbuild today is

going to look like it was sized wrong in

just a year or two here. The agentic era

is going to make everything we've spent

so far look like a little down payment

on what we need to spend. You know

what's interesting? This pattern is

fractal. Just as the infrastructure

inversion pattern plays out at scale

with these big model makers, it plays

out for all of us as individuals. And

the question it forces at each of those

scales is the same. What do you have

that's valuable when the infrastructure

shifts underneath you? Google is

spending $185 billion because they've

calculated that the cost of

underbuilding is existential. Not risky,

existential. They'd rather be wrong and

have spent too much than be right and

have spent too little. Your career works

the same way. And the question you need

to answer honestly is what human skills

survive when agents can code for months.

When they can review contracts, when

they can generate production quality

work at machine speed. I'm going to

suggest four things. First, everyone

talks about it, but we're going to get

into it. Taste. The ability to look at

what an agent produces and know not just

analytically, not just by checklist, but

by a hard one instinct whether it's

right, whether it's good, whether it

solves the real problem or a poorly

framed problem. Agents can generate

enormous volumes of competent output. We

will be drowning in competent output

before long, but they cannot yet tell

the difference between competent and

extraordinary reliably. They cannot tell

the difference reliably between

technically correct and strategically

right. The people who can make that

distinction, who have refined their

judgment through years of doing the

work, become exponentially more valuable

when the cost of generating options

drops to zero. Taste becomes a filter.

Number two, exquisite domain judgment,

not general intelligence. Agents are

going to have that in abundance. The

specific, contextual, hard to articulate

understanding of how a particular domain

actually works. The lawyer who knows

which clauses matter in the negotiation,

not just which clauses need to exist.

The engineer who knows which

architectural decisions are going to

create pain in 18 months or 30 years.

The executive who knows which market

signals are noise and which are

structural. This knowledge is

accumulated over years and encoded in

intuition that agents can approximate

but not yet replicate because it depends

on experience that is just not in the

training set. Phenomenal ramp is another

skill. the ability to learn fast when

everything is evolving fast, not I took

a course on AI. It's the kind of

learning where you're using the tools

daily, your mental model is updating

weekly, and you're comfortable operating

at the frontier of capability, even when

the frontier moved since last Tuesday.

In a world where Opus 4.6 can come on

the scene and everybody will be talking

about it and Codeex will follow 20

minutes later and then who knows what

drops next week, it's the ability to

absorb change at speed that matters.

That's a meta skill that makes all the

other skills usable. The humans who can

keep up with AI have an edge that just

keeps compounding. And last but not

least, we need relentless honesty about

where value is moving. This is the hard

one because it requires looking at our

own work and asking which parts of it

are really valuable and which parts an

agent could handle better, cheaper, and

faster. Most people don't want to do

this inventory. It can be heartbreaking.

It can be threatening. It can require

admitting that some of the skills you

spent years building, they're

depreciating so fast it's worthless. But

the people who do the inventory, who do

the work, who are honest about which

parts of our work, taste and judgment

matter in, and which parts execution and

process are the only things and which

parts are just execution and process.

Those are the ones who can reallocate

their time toward the things that still

matter before the market forces them to.

If you're waiting for AI to settle down

before investing serious time and

skills, please don't. You will not come

back from that bet. You are making the

same bet as the companies that waited

for cloud computing to prove itself in

2008. Stability is not coming. The pace

is accelerating. It's not slowing down.

And the gap between I use AI tools and I

have rebuilt how I work around what AI

makes possible is really the individual

version of the gap between we added AI

features to the product and we built our

architecture to be agent first. The

first approach feels productive. The

second approach is what is actually

going to change our outcomes. This is

now an agentic world. This is year one.

The $185 billion Google is spending is

not reckless. It's not aggressive. It's

probably not enough. The market is going

to look back on 2026 the way we looked

back at the early AWS data centers, the

first transcontinental railroad, the

fiber optic cables lying in the dark

under the Atlantic. The foundation of

everything that comes next is being

built this year. And it's being laid in

the year that agents proved they were

real. And that matters as much for you

and me as it does for those fancy

companies spending those hundreds of

billions of dollars. Good luck out

there. I put together an agent guide for

this one because because the more we

practice, the better off we're going to

be.

Interactive Summary

Ask follow-up questions or revisit key timestamps.

The video details the massive, unprecedented investment by tech giants like Google into AI infrastructure, totaling hundreds of billions, driven by the rapid emergence and deployment of AI agents. Initially met with market skepticism, this spending is now understood as crucial, shifting from model training to continuous, large-scale inference. Unlike previous infrastructure booms such as railroads or fiber optics, AI infrastructure integrates intelligence, allowing providers to capture value directly from applications built on top. The timeline for this buildout is significantly compressed, forcing companies to quickly become platform builders. In this agentic era, key human skills like taste/judgment, exquisite domain knowledge, rapid learning, and honest value assessment will remain vital as AI agents become increasingly autonomous.

Suggested questions

4 ready-made promptsRecently Distilled

Videos recently processed by our community