UMAP explained simply

Now Playing

UMAP explained simply

Transcript

438 segments

We will here have a look at UMAP which

is a similar method to the TE method

that I covered in a previous video. UAP

stands for uniform manifold

approximation and projection which is a

dimension reduction method that captures

both local and global structures of

highdimensional data. The UMAP method

was published in 2018.

I will first show some applications

where UMAP can be used and compare it

with principal component analysis. Then

we will have a look at the simple

example that explains the basic math

behind UMAP. We'll first see how UMAP

and PCA perform on a classical amnes

data set which contains thousands of

images of handwritten digits. Every row

in this data set contains pixel values

between 0ero and 255 for each image. The

first column shows which digit the image

contains. For example, the first row

represents an image of a handwritten

five whereas the second row represents

an image of a handwritten zero and so

forth. Each image is a square that

contains 784 pixels, which means that

each image or row has 784 columns in

addition to the first column. Suppose

that we like to generate an image of the

data that is located on row number six.

We would then put the elements in column

numbers 2 to 29 here. Then the next 28

elements here, and so forth.

until we have a square matrix with 28

rows and columns. This image is supposed

to represent a handwritten two. We'll

now use UMAP and PCA to compress these

784 columns into just two columns and

plot these columns in a two-dimensional

plot.

We will then label the points in the

plot so that we can see which point that

corresponds to a certain digit. Similar

to PCA, UMAP is an unsupervised method

because it does not use these labels in

its computation to separate groups or

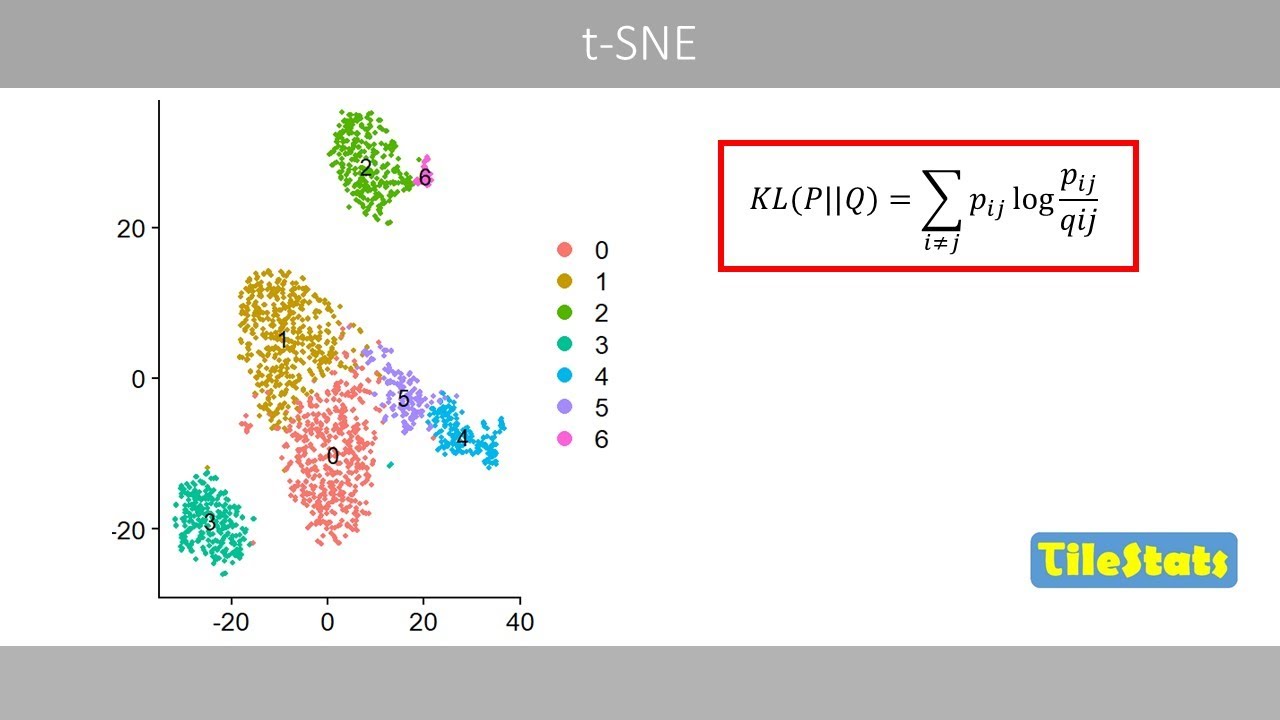

clusters. This is an example of a UMAP

plot of 10,000 images in the MNEST data

set. Each point in this image represents

one image. For example, this point

represents the following handwritten

eight

whereas this point represents a four. We

can see that the UMAP separates the

images of the 10 digits quite well. In

comparison, this is the corresponding

PCA plot of the MNEST data set which

fails to separate the digits. I will

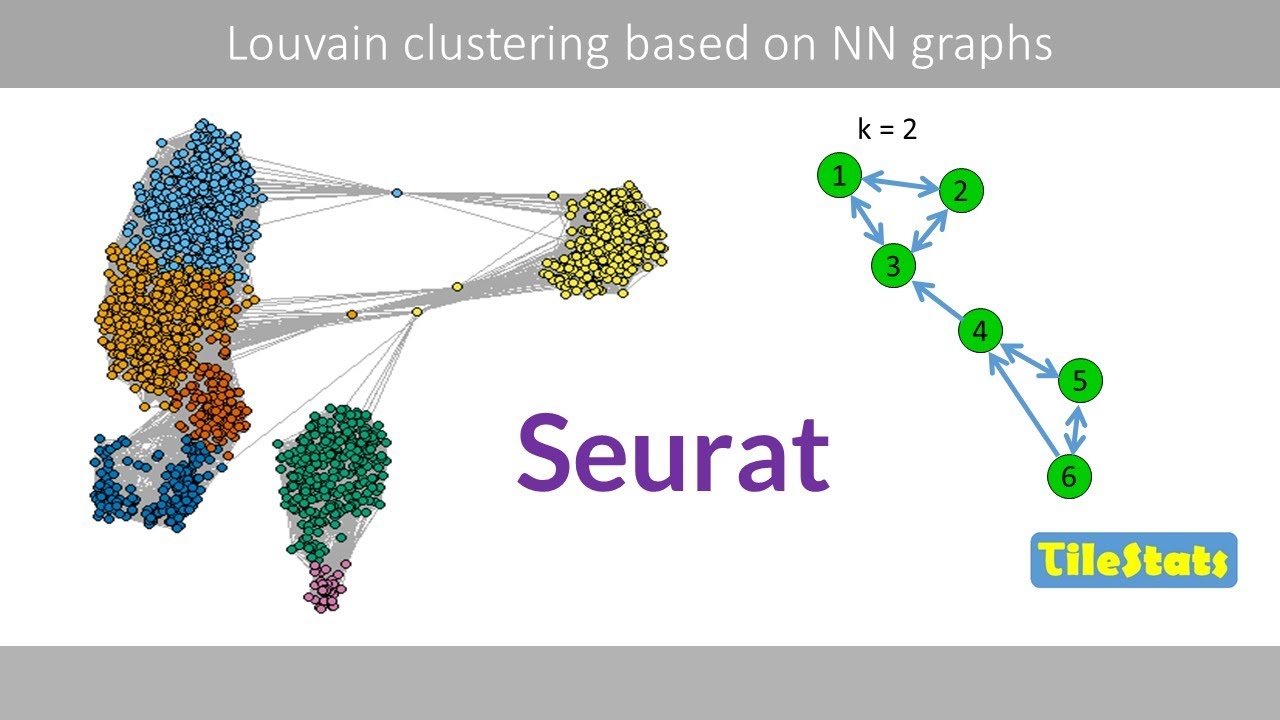

explain why in a minute. Um plots are

commonly used in single cell RNA

sequencing to visualize highdimensional

gene expression data in two dimensions

to identify clusters of cells with

similar expressed genes. Each point in

this um plot represents a single cell.

Points in the same cluster can be seen

as cells that have a similar gene

expression profile. Such a cluster of

cells therefore usually represent cells

of the same cell type. For example, the

clusters may represent different cells

in our immune system. If you were to use

PCA on the same data set, the clusters

would not separate well. So why is this

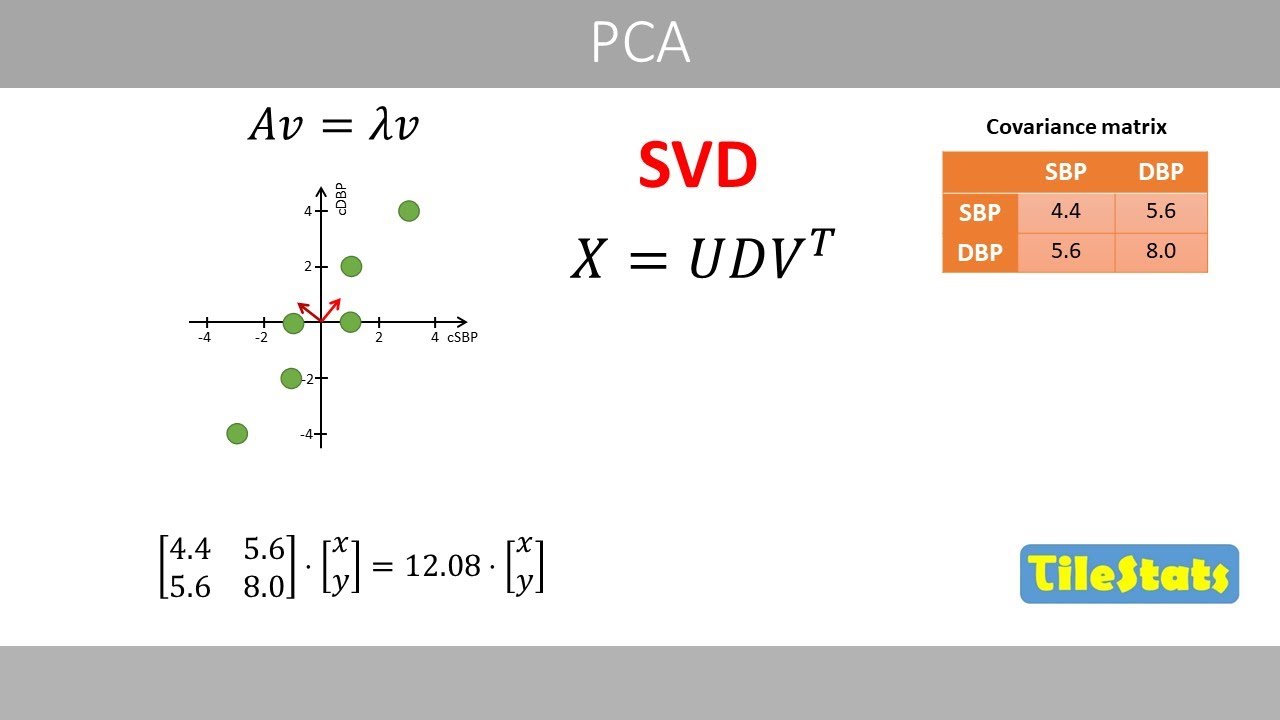

the case? Well, one reason is that a PCA

plot usually only shows the first two

principal components because these

explain most of the variance. By

illustrating only the first two

components, which in this case only

explain about 5% of the total variance,

we lose a lot of information that is

stored in the other components.

For example, we can see that cluster two

and six are not well separated based on

the first two principal components. If

you instead plot component one versus

component five, clusters two and six are

now well separated. The um method does

not hold important information in

several components like this. Instead,

it includes all information in just two

dimensions, which explains why the UMAP

plot better identifies clusters that

exist in the highdimensional data.

However, the UMAP method is

computationally expensive, which is why

it is sometimes combined with PCA. One

can therefore compress the variables by

first using PCA and selecting for

example the first 30 to 50 components

that store most information and then

computing the UMAP based on these

components instead of all variables.

Another reason why PCA might fail to

separate existing clusters is that it is

a linear method. For example, if we were

to project this nonlinear

two-dimensional data set into one

dimension, the clusters will not

separate well with PCA.

Whereas the UMAP would do a good job in

separating the existing clusters because

it preserves local nonlinear

relationships.

Although these points are fairly close

in the global geometry, UMAP tries to

preserve also the local structure.

Close points are assigned a high

connectivity weight indicating a strong

likelihood of being neighbors which

means that also these points have a high

connectivity weight and so forth.

A UMAP is controlled by these two

hyperparameters

that are set by the user. The parameter

ns can be seen as the number of

neighbors each data point selects for

its local neighborhood in the

highdimensional space. The effect of

this parameter is shown on the amnest

data set. A small value focuses more on

local structures which might fragment

some clusters.

A larger value focuses the plot more on

the global structure where clusters may

overlap a lot. The default value of 15

is usually a good value to use that

captures both local and global

structures.

The parameter mean distance controls the

minimum distance between points in the

lowdimensional space that I will explain

later on. A low value results in tight

clusters

whereas a two high value might cause

overlapping clusters.

Setting these two parameters to 15 and

0.2 gives a nice um plot based on the

amnes data set.

The parameter spread was not described

in the original UMAP paper but has been

included in several implementations to

control the distance between the

clusters. Increasing the value of this

parameter increases the distance between

the clusters in the MNEST data set. We

will now discuss the basic math behind

UMAP.

The math that I will show comes mainly

from appendix C in the paper where they

explain U mapap in a similar way to the

tney method which is a lot simpler to

understand.

We will use a similar three-dimensional

data set as in the video about Tney and

use the same random initial coordinates

in two dimensions.

UMAP may either use initial random data

points like this or points initialized

based on the method of spectral

embedding.

We'll here see how UMAP reduces the

dimensions of this highdimensional data

into lowdimensional data. In other

words, how it reduces three-dimensional

data into two-dimensional data. In

comparison to Tesney, which uses a

Gaussian like distribution that I

explained in the Tesney video, um uses

an exponential kernel based on some

distance metric. I will here use the

Cleian distance. Um uses this equation

to compute a symmetric matrix whereas

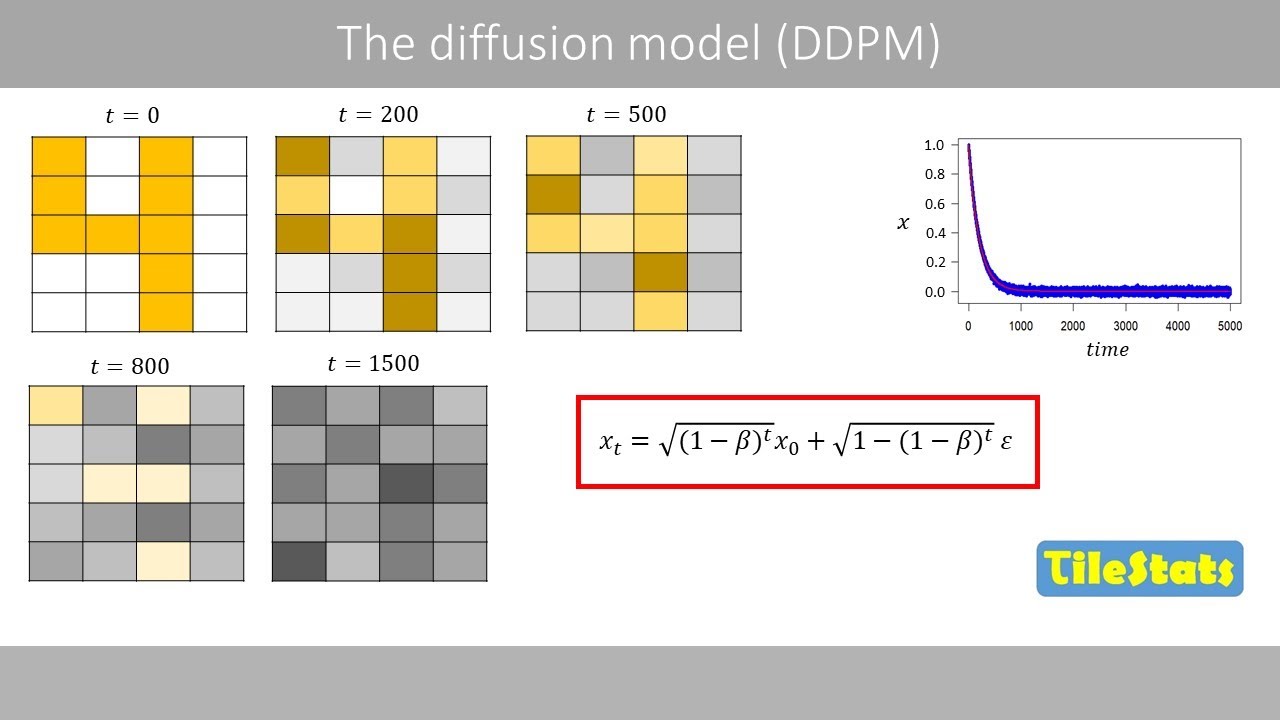

Tney uses this equation. UMAP starts by

calculating for example the client

distances between all data points of the

original data in the highdimensional

space.

For example, if we were to calculate the

client distance between data points one

and five. We will plug in the X, Y and Z

coordinates in this equation

and do the math. We now plug in the

rounded ecclesian distance in a distance

matrix.

If you calculate the distances between

all data points in our data set, we

would get the following values. For

example, we can see that the ecclesian

distance between data points two and

four is 5.19.

Let's put the cleon distances based on

the highdimensional data set here.

Next, we determine the value of K, also

called N neighbors. The default value is

usually 15, but since we have a small

data set, we set this value to three.

This means that when we consider, for

example, the distances between data

point one and all the other four data

points, we only focus on the three

closest points to data point number one.

For example, these are the three closest

neighbors to data point number two. And

these are the three closest neighbors to

data point number three. And so forth.

For data point one, we plug in its

shortest distance here, which is its

distance to data point number three. And

then we plug in the distance between

data point one and two. Here we set

sigma to one for now and do the math.

Then we plug in the distance between

data points one and three. We skip this

distance because data point 4 is not one

of the three closest points to data

point one. Finally, we plug in the

distance between data points one and

five.

If you do the math in the numerator,

we will get these values. This is an

exponential distribution where sigma

determines the area under the curve.

Since sigma is set to one, the area

under the curve is now one. If you plug

in the calculated values in the

numerators in the exponential

distribution,

we can see that the heights of the curve

correspond to these values.

Sigma is now optimized

so that the sum of the heights

is equal to the log base 2 of the

hyperparameter ns.

Remember that we previously set the

hyperparameter n neighbors to three.

Sigma is now adjusted

so that the sum of the heights

is equal to 1.58.

If you set sigma to 0.648,

the sum will be equal to about 1.58.

Note that the area below the curve is

now 0.648.

Since the area below the car must be

equal to one to be defined as a

probability distribution, the

unnormalized exponential function used

in UMAP is instead referred to as an

exponential kernel. This is the adjusted

VIGs for different optimized values of

sigma for each row. Note that every row

now sum ups to about 1.58.

These dots represent the distances that

we did not consider because they were

not among the three closest neighbors.

This is therefore a sparse matrix. A

sparse matrix is more computationally

efficient to work with because the

memory use is n * k instead of n * n.

These elements, including data points

that are not the three closest

neighbors, are set to zero.

Next, we symmetriize this matrix by this

equation where the symmetric distance

value between for example data points 2

and 4 is equal to 0.2993.

If you do the same calculations for the

other values, we will get these values.

Note that the upper triangle

holds the same values as in the lower

triangle, which means that we have a

symmetric matrix.

These are the normalized distances for

the highdimensional data that will be

compared with the distances of the

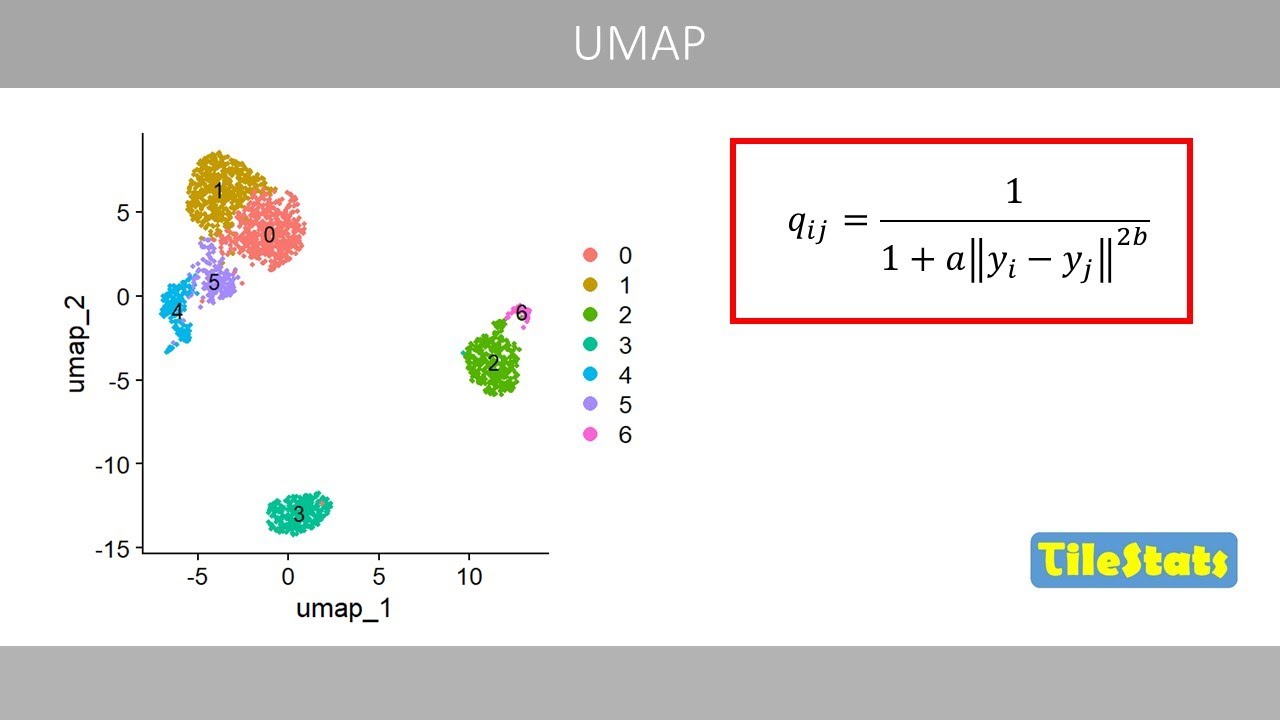

lowdimensional data. Next, we compute

the distances for the lowdimensional

data with this equation. This equation

has two parameters that are optimized

based on the hyperparameter mean

distance that is set by the user. I will

explain how these values are calculated

at the end of this video. If you set the

hyperparameter mean distance to 0.5.

A will be equal to 0.576

and B will be equal to 1.363.

If a and b are set to one, we'll get the

same expression as in the numerator of

the corresponding equation for the tnne

method. We start by calculating the

cleian distance between the points in

the low dimensional space. These are our

initial random coordinates in two

dimensions.

To calculate the cleon distance between,

for example, data point one and three in

the low dimensional space, we plug in

the x and y coordinates and do the math

and plug in the resulting value in the

distance matrix. If you calculate the

distances between all data points, we

will get this matrix.

We can now plug in the client distances

in this equation and compute the first Q

value like this which we plug in into

the Q matrix.

If we compute the other values, we'll

get the following Q matrix in which the

main diagonal is set to zero. These

values will be adjusted by comparing

them

with the values in our previous

symmetric V matrix based on

highdimensional data by using the

following cross entropy cost function

that we minimize with the gradient

descent method.

We here only need to include the values

in the upper triangles.

If we compute the value of the cost

function based on the upper triangles,

we get a value of about 7.7.

We'll now change the coordinates of the

points in the lowdimensional data

and update the values in the Q matrix

to reduce the value of the cost

function. UAP uses stochastic gradient

descent to do this. But to simplify the

calculations, I've here just used the

gradient descent method.

To compute the gradient descent, we need

to find the derivative of this function,

which looks like this. We know the

values of A and B and the values in the

V and Q matrices and the coordinates of

the points in the low dimensional data

and the corresponding ukian distances.

We'll here see how to calculate the

derivative based on the first data

point.

We plug in these values

here

and then these values

here.

Then we plug in the clear distances

between data point one and all the other

data points

here.

Next, we plug in the x and y coordinates

of data point one and the coordinates of

the other data points

and do the math.

Note that this calculation is based on

more exact numbers of the values in the

Q matrix and the distance matrix.

If you do the calculations for all rows,

we'll get these values

which we plug in into the gradient

descent formula

where alpha is the learning rate that we

here set to 0.01.

These are our current coordinates in the

low dimensional space.

So if we multiply these values by the

learning rate and subtract the resulting

values from these values,

we'll get these updated values.

And the coordinates of the data points

will therefore be updated like this.

Note that data points four and five have

now moved closer to each other so that

the location of the points in the low

dimensional space are similar to the

ones we see in the high dimensional

space.

With these updated values, we have

reduced the cost function from 7.7 to

6.9.

If we repeat the same calculations 200

times, we'll get the following plot

which closely resembles what we see in

the highdimensional space.

After 200 iterations, these are the

values in the Q matrix which closely

match those in this matrix.

Finally, I will explain how the

parameter mean distance is related to

the parameters A and B. The red curve is

the target curve that takes the exact

shape based on the parameter mean

distance. The mean distance controls the

length of the flat part of this curve.

If the distance is shorter than or equal

to the mean distance parameter, the

value of the curve is equal to one. And

if the distance is longer, the curve

follows an exponential decay function.

Now we use nonlinear regression to fit

this function to the points on the

target curve for a range of different

distances

so that we get the following fitted

curve where a and b are estimated to the

following values. If you will plug in

these values here and change the value

of d between zero and six we would get

this blue curve. So when we plug in the

distances in this function, it can be

seen as we compute the heights of this

fitted curve based on the distances

between for example data point one and

the other data points.

If you increase the mean distance from

for example 0.5 to one, the flat part of

the fitted curve increases and the

distances between the data points

increase so that we get about the same

optimal Q values.

The points are therefore forced to keep

more distance between them when we

increase the parameter mean distance.

This explains why the data points are

more spread out within the clusters when

we increase the parameter mean distance.

This was the end of this video about

UMAP. Thanks for watching.

Interactive Summary

Ask follow-up questions or revisit key timestamps.

This video explains UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection), a dimension reduction technique that captures both local and global structures of high-dimensional data. It compares UMAP with Principal Component Analysis (PCA), demonstrating UMAP's superior performance in separating clusters in datasets like handwritten digits (MNIST) and single-cell RNA sequencing data. The explanation delves into the mathematical underpinnings of UMAP, including how it constructs a high-dimensional graph using an exponential kernel and then optimizes a low-dimensional representation using cross-entropy. Key hyperparameters like 'n neighbors' and 'min distance' are discussed, along with their impact on the resulting visualizations. The video also touches upon how UMAP can be combined with PCA for computational efficiency and explains the role of the 'spread' parameter.

Suggested questions

3 ready-made promptsRecently Distilled

Videos recently processed by our community