t-SNE explained: Visualizing High-Dimensional Data

Now Playing

t-SNE explained: Visualizing High-Dimensional Data

Transcript

484 segments

In this video, we will have a look at

the TNE method which can be used for

visualizing highdimensional data in for

example two dimensions. TNE or TSN

stands for T distributed stochastic

neighbor embedding which is a method

that captures local structures of

highdimensional data while also

revealing the global structure such as

the presence of clusters. The Tney

method was published in 2008 and the

equations that I will show at the end of

this video are given according to this

paper and from Wikipedia. I will first

show some applications where Tesnney can

be used and compare it with principle

component analysis. Then we will have a

look at the simple example that explains

the basic idea behind Tesney before we

go into the mathematical details.

We will first see how TNE and PCA

perform on the classical Amnes data set

which contains thousands of images of

handwritten digits.

Every row in this data set contains

pixel values for each image. The first

column shows which digit the image

contains. For example, the first row

represents an image of a handwritten

five, whereas the second row represents

an image of a handwritten zero and so

forth. Each image is a square that

contains 784 pixels, which means that

each image or row has 784 columns in

addition to the first column. Suppose

that we like to generate an image of the

data that is located on row number six.

We would then put the elements in column

numbers 2 to 29 here. Then the next 28

elements here and so forth

until we have a square matrix with 28

rows and columns. This image is supposed

to represent a handwritten two.

We will now use TNE and PCA to compress

these 784 columns

into just two columns and plot these

columns in two-dimensional plot and

label the points so that we can see

which point that corresponds to a

certain digit just like PCA tney is an

unsupervised method because it does not

use these labels in its computation to

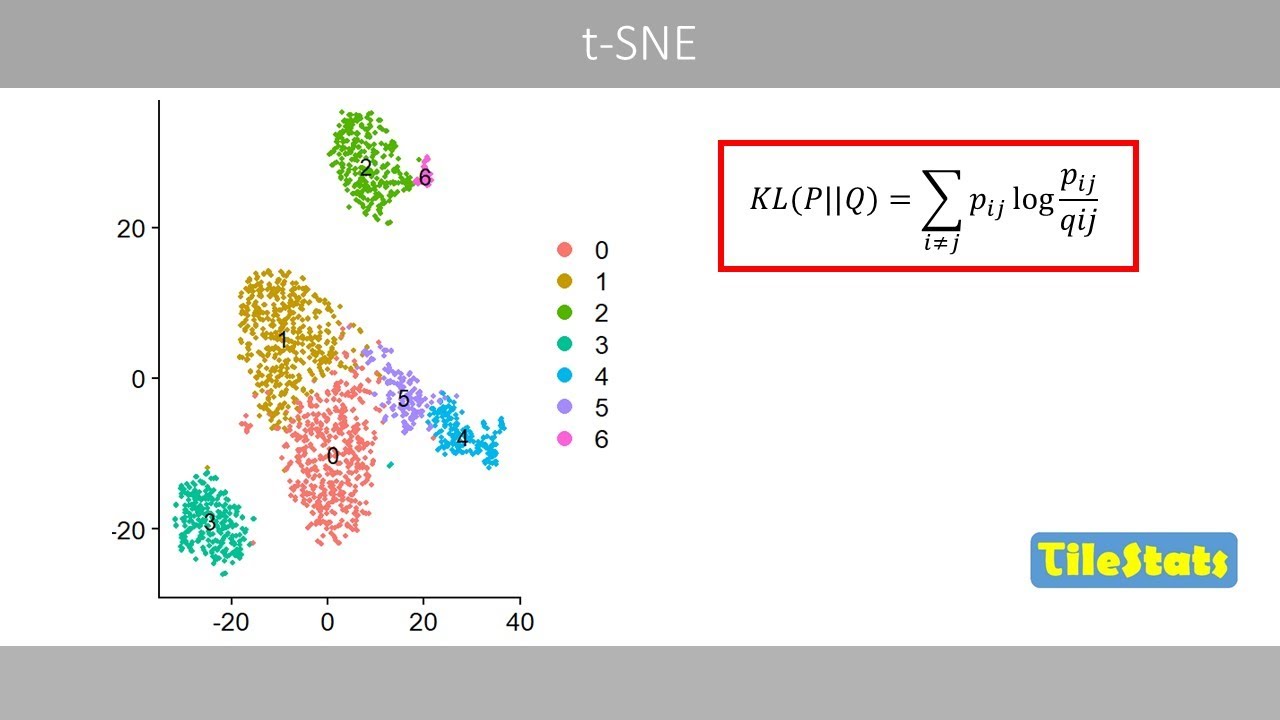

identify the groups. This is an example

of a teas plot of 10,000 images in the

amnes data set. Each point in this plot

represents one image. For example, this

point represents the following

handwritten eight whereas this point

represents a four.

We can see that the tin plot separates

the images of the 10 digits quite well.

In comparison, this is the corresponding

PCA plot of the AMNES data set which

fails to separate the digits. I will

explain why in a minute.

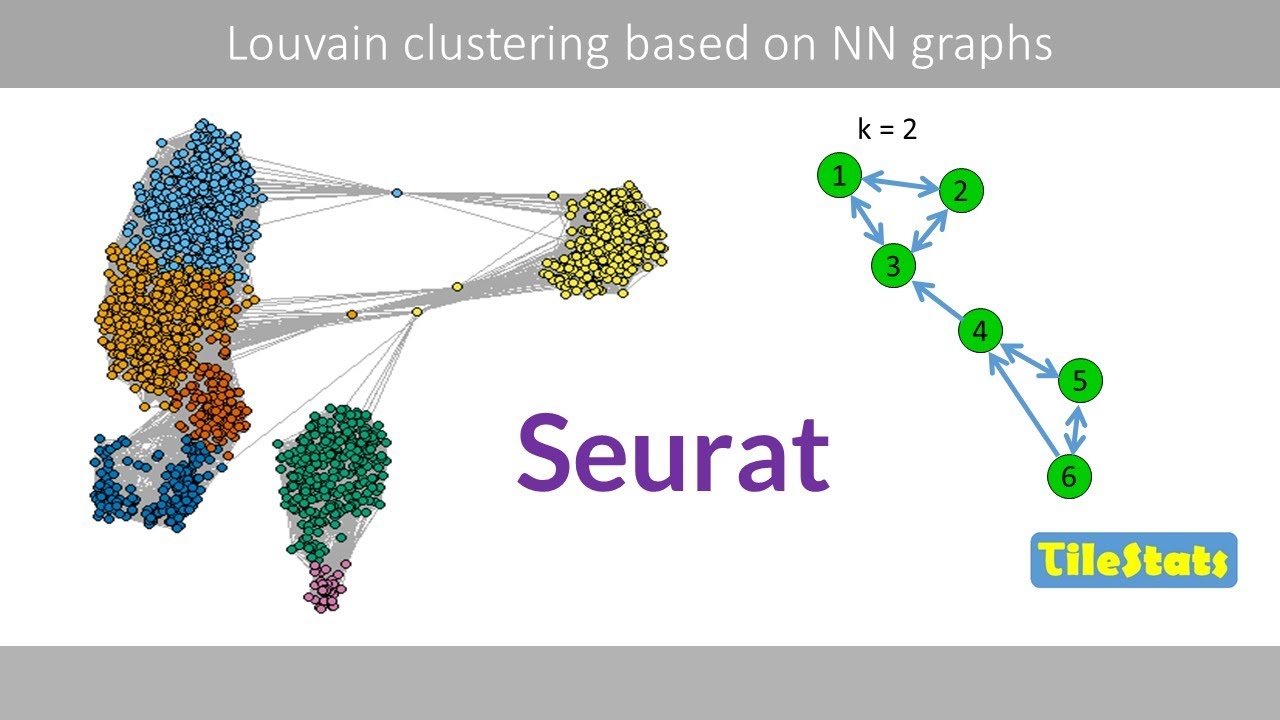

Tnip plots are commonly used in single

cell RNA sequencing to visualize

highdimensional gene expression data in

two dimensions to identify clusters of

cells with similar expressed genes.

Each point in this tney plot represents

a single cell. Points in the same

cluster can be seen as cells that have a

similar gene expression profile. Such a

cluster of cells therefore usually

represent cells of the same cell type.

For example, the clusters may represent

different cells in our immune system.

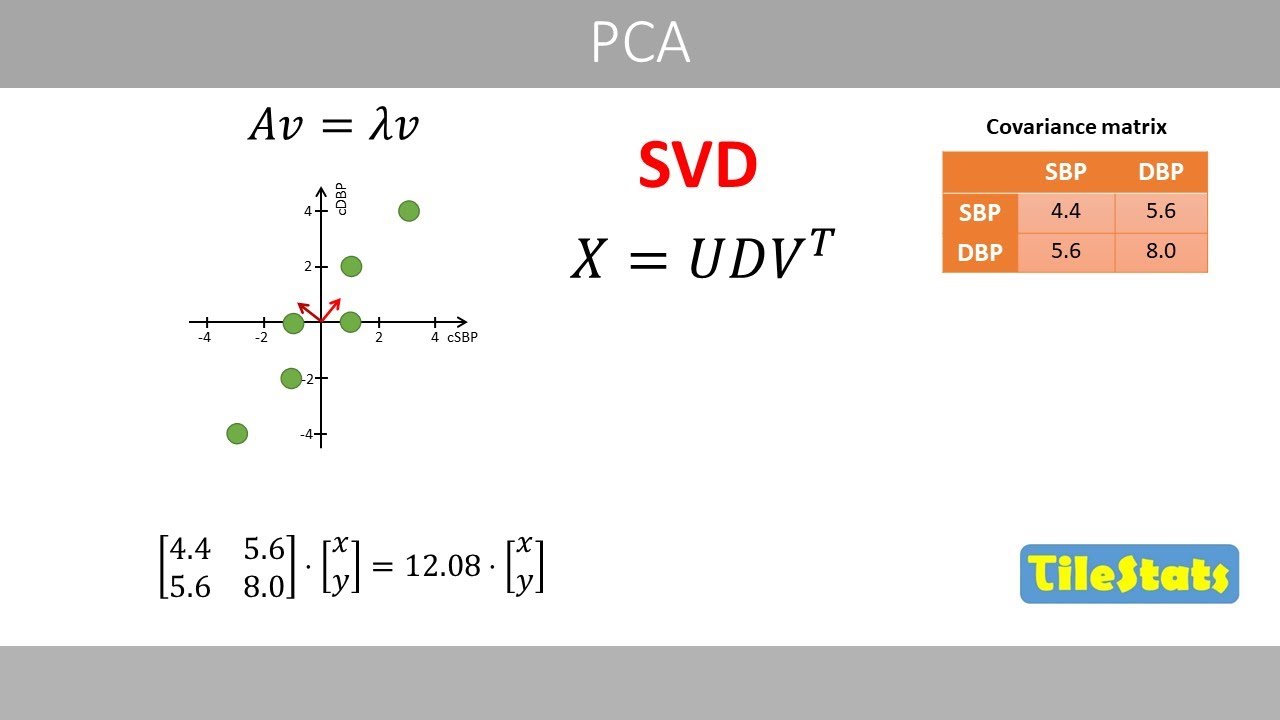

If you were to use PCA on the same data

set, the clusters would not separate

well. So why is this the case?

Well, one reason is that a PCA plot

usually only shows the first two

principal components because these

explain most of the variance.

By illustrating only the first two

components, which in this case only

explain about 5% of the total variance,

we lose a lot of information that is

stored in the other components. For

example, we can see that clusters two

and six are not well separated based on

the first two components.

If you instead plot component one versus

component five, clusters two and six are

now well separated. The TD method does

not hold important information in

several components like this. Instead,

it includes all information into just

two dimensions, which explains why the

TED plot barely shows the clusters that

exist in the highdimensional data.

However, the TS method is

computationally expensive, which is why

it is sometimes combined with PCA. One

can therefore compress the variables by

first using PCA and select for example

the first 30 to 50 components that store

most information and then computing the

Tnney plot based on these components

instead of all variables.

Another reason why PCA might fail to

separate the existing clusters is that

it is a linear method. For example, if

you were to project this nonlinear

two-dimensional data set in one

dimension, the clusters will not

separate well with PCA. Whereas the TI

method would do a good job in separating

the existing clusters because it

preserves local nonlinear relationships.

All of these points are fairly close in

the global geometry. Disney tries to

preserve the local neighborhoods. Points

that are close have a high probability

of being neighbors, which means that

these points have also a high

probability of being neighbors and so

forth.

Another example where Tesney is commonly

used is to visualize word embeddings.

This is the same data that I showed in

the video about transformers.

The GPT model had about 12,000 embedding

dimensions.

If we were to compress thousands of word

embedding dimensions into just two by

using Tesney, we would get the plot like

this where every point represents a word

or a token. For example, this plot shows

5,000 words. Similar words are close in

this Tesnney plot because their

highdimensional embeddings have similar

features or contextual meanings.

So when you see a Tesney plot like this,

you can interpret it like points that

are close together in the Tesnney plot

were likely close neighbors in the

original highdimensional space.

However, you should not use the plot to

compare distances between clusters. For

example, eights and sixes in amnes data

set are here far apart, although they

are expected to be close in a

highdimensional space since such

handwritten digits should be quite

similar. Also, do not try to interpret

the numbers on the axis because these

values do not mean anything. We will now

have a look at the very simple example

to illustrate the basics of how tis

works before we go into its exact

mathematical details.

Suppose that we have the following

simple three-dimensional data set with

five data points which can be visualized

like this in a three-dimensional scatter

plot. We see that data points four and

five are close

whereas data points one two and three

are close. The idea is to project these

data points into two dimensions so that

we can visualize the data in a simple

two-dimensional scatter plot. In tis the

highdimensional space refers to the

original data whereas the lowdimensional

space is a simplified representation

that preserves the local similarities

between the points. The method starts by

calculating the client distance between

all data points of the original data.

For example, if we were to calculate the

distance between data points one and

five, we would plug in the x, y, and z

coordinates in this equation and do the

math.

We now plug in the rounded ukidian

distance in a distance matrix. If we

calculate the distances between all data

points in our data set, we would get the

following values. For example, we can

see that the ecclesian distance between

data points 2 and 4 is 5.2.

Then we might normalize these distances

by for example dividing all the values

by the maximum value in this matrix so

that we get the following values.

Next, we place five data points at

random coordinates in a two-dimensional

space and calculate the client distance

between the points. For example, to

calculate the distance between data

points one and three,

we plug in the x and y coordinates of

these two data points and do the math.

Next, we normalize the distances by

dividing by the maximum value in this

matrix.

so that we get these values. The reason

why we normalize is that we can now

better compare the distances.

Data points in high dimensions have

generally longer distances to each other

than in low dimensions, which explains

why we normalize the distances. The idea

is now to move around these data points

so that the normalized distances in two

dimensions are as close as possible to

the normalized distances in the high

dimensional space. For example, we can

see that the normalized distances

between data points two and three differ

quite much in the high and low

dimensional space. Let's move this data

point from here

to here and recalculate the normalized

distances. We see that the distances now

become more similar to the normalized

distances in three dimensions, which

means that the points in the

two-dimensional plot now better resemble

the points in the highdimensional space.

If we continue to move around the data

points, we might end up with the

following plot that looks quite similar

to the plot in three dimensions. We also

see that these two matrices now have

similar values.

We will now have a look at the math

behind TES.

The method starts by calculating the

Eian distances between the data points

in the highdimensional space. Just as we

did before, the distances are here shown

with two decimal places. Note that I

also fill the upper triangle of this

matrix. And you will see why soon. So

these values are the same because they

both represent the distance between data

points one and three.

Next, we square the distances.

We'll now calculate the conditional

probabilities

where these terms correspond to our

squared distances.

This formula can be used to calculate

the normal distribution.

So what we have up here is similar to

this part of the formula for the normal

distribution.

So the numerator can be seen as the

height of a normal or Gaussian

distribution for a given distance

between two data points. where sigma

squar represents the variance which

controls the width of the normal

distribution to simplify the calculation

I will here use a fixed value of sigma

so that these two terms are equal to one

in tney the value of sigma is not fixed

and is related to the so-called

perplexity parameter that I will explain

at the end of this video let's apply

this formula to Calculate the

conditional probability in row two,

column 1. We plug in the squared

ecclesian distance between data points

one and two. Here what we get in the

numerator can be seen as the height of

the Gaussian curve for the squared

ecclesian distance between data points

one and two. Then we plug in the values

of the second row in the denominator but

not for the distance between a data

point and itself. This term can be seen

as the height of the Gaussian curve

based on the distance between data

points one and two. And this is the

height based on the distance between

data points two and three.

The heights that correspond to the

distances from data point two to data

points four and five will be super

small.

If you do the math, we get the value of

about 0.39

which we plug in into a matrix with

conditional probabilities.

If we compute the whole matrix, we'll

get these values where each row now sum

ups to one.

So this row can be seen as conditional

probabilities that data point one would

pick one of the other four data points

as its neighbor.

For nearby data points the conditional

probability is high whereas for data

points further away the conditional

probabilities will be super small for

reasonable values of sigma.

So the tney method can be seen as it

uses large parise distances between the

similar data points and small parise

distances between similar data points.

Note that the values for data points one

and three are different.

One therefore computes the average of

these two values and also divides by the

sample size.

In this case, we get a value of 0.11

that we plug in here. Then we compute

the same for the other elements.

We now have a symmetric matrix where all

its values now sum up to one. We are now

done with all the calculations for the

highdimensional data. Let's put it here

as a reference.

Next, we place five data points in a

two-dimensional space with random

coordinates, which explains why tney is

a stochastic method because the initial

coordinates will be different every time

we create a new plot. Then we calculate

the squared ecclesian distances between

the five data points in the

lowdimensional space.

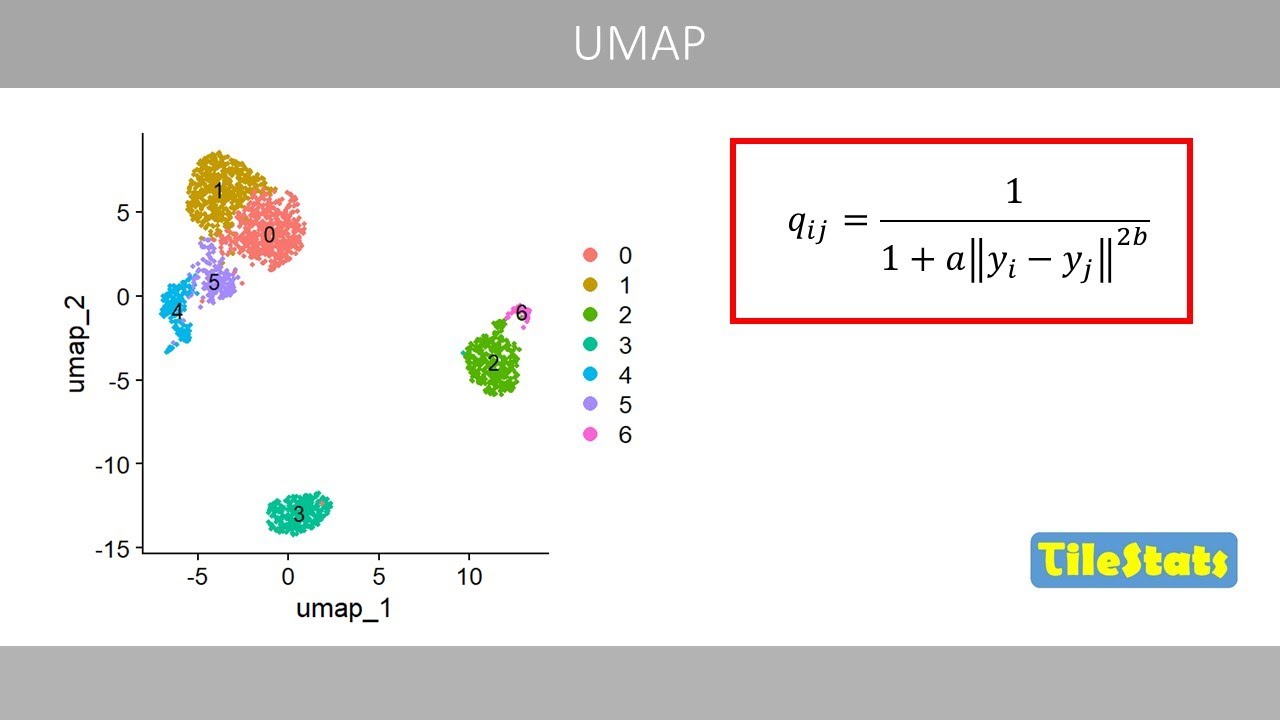

We can now use the same equation based

on the Gaussian distribution as we used

previously where sigma is set to one

over the square root of two so that this

equation no longer depends on sigma.

However, we will then generate an SN

plot which tends to squeeze the points

too much which causes the crowding

problem as explained in the te paper.

They therefore used a formula based on

the t distribution with one degree of

freedom which will generate the tney

plot. The t in the name tney therefore

refers to the t distribution.

The reason for instead using the t

distribution with one degree of freedom

is that it is wider compared to the

gaussian distribution.

So to compute the value of the Q matrix,

for example, for the third row, first

column, we plug in the squared eidian

distance here

and all the other values in this matrix

that are not included in the main

diagonal in the denominator.

We then fill in this value in the Q

matrix.

If you do the same calculations for the

other elements in this matrix, it will

include these values which should sum up

to one. So the idea is now to move

around these data points so that the

values in the Q matrix become as similar

as possible to the ones in the P matrix.

This can be done by minimizing this cost

function.

If the values in the two matrices are

identical, the value of this ratio will

be equal to one. And since the log of

one is zero, the cost function would

then be equal to zero, which means that

the two matrices are identical.

Let's plug in our values except for the

values in the main diagonal to compute

the value of this cost function.

We see that our cost function results in

a value of 0.77.

What is interesting with this cost

function is that it will generate a

large penalty for a large pig if the

corresponding Q is too small.

This means that the cost function mainly

focuses on the corresponding errors for

points that are closed in the

highdimensional space which is one

reason why tney strongly preserves the

local neighborhoods

to reduce the value of this cost

function. We can use the method of

gradient descent. We therefore need to

compute the derivative of this function.

This is the derivative of the cost

function that we can use in the gradient

descent method. How to derive this

function can be found in the original

tney paper.

These are our P and Q matrices and the

Y's are the coordinates of the given

data points in the low dimensional

space.

We now plug in our values in this

function for the first row where I is

equal to one and J is equal to two.

Now J is increased by one which means

that we take the corresponding values in

the third column.

Then we increase J to four

and five and do the math which here show

values from calculations with more

decimals.

Then we increase I to two and do the

same calculations.

If you do the calculations for all rows,

we will get these values

which we plug in in the gradient descent

formula. where alpha is the learning

rate that were here set to one. These

are our current coordinates in the

lowdimensional space.

In the paper, they also added a momentum

term for a smoother update, but we will

not use that term here. So if you

substract these values

from these values, we'll get these

updated values

and the coordinates of the data points

will be updated

like this. With these updated values, we

have reduced the cost function from 0.77

to 0.56.

We then iterate like this until we reach

some convergence or until we reach the

maximum number of iterations.

After 100 iterations,

I got the following plots that closely

resembles what we see in the

highdimensional space. After 100

iterations,

these are the values in the Q matrix,

which closely match those in the P

matrix.

So the main idea with the teasing method

is to minimize the difference between

the distances based on the conditional

probabilities in the high and low

dimensional space to preserve both local

and global structures in the data.

Finally, we will discuss the perplexity

hyperparameter.

Remember that we previously used a fixed

value of sigma. Tney does not use the

same sigma for all points.

So for each point we find an appropriate

value of sigma so that two to the power

of the Shannon entropy of the

conditional probabilities is

approximately equal to the chosen

perplexity parameter. A larger

perplexity parameter generally results

in larger values of sigma. The

recommended value of the perplexity

parameter is in the range of 5 to 50.

So here are three plots of the amnes

data set which show how the perplexity

parameter changes the plots.

If you set the perplexity parameter to

five, the clusters are much closer than

if you set a larger value of the

perplexity parameter.

So you need to try a few values of this

parameter until you find an appropriate

plot that you like to show. Note that

there is a related method called UAP

which produces similar plots as the TE

method. I will explain the UMAP method

in a future video.

This was the end of this video about the

TES method. Thanks for watching.

Interactive Summary

Ask follow-up questions or revisit key timestamps.

This video explains the T-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (T-SNE) method, a technique used for visualizing high-dimensional data in lower dimensions, typically two. It contrasts T-SNE with Principal Component Analysis (PCA), highlighting T-SNE's ability to preserve local structures and reveal global patterns like clusters, which PCA often fails to do. The explanation covers applications in datasets like MNIST digits and single-cell RNA sequencing, as well as word embeddings. The video then delves into the mathematical details of T-SNE, including the calculation of conditional probabilities, the use of a cost function based on the Kullback-Leibler divergence, and the optimization process using gradient descent. Finally, it discusses the perplexity hyperparameter and its effect on the resulting visualization, mentioning UMAP as a related method.

Suggested questions

8 ready-made promptsRecently Distilled

Videos recently processed by our community