Dario Amodei — “We are near the end of the exponential”

Now Playing

Dario Amodei — “We are near the end of the exponential”

Transcript

1480 segments

We talked three years ago. In your view, what has been the biggest update over the last three years?

What has been the biggest difference between what it felt like then versus now?

Broadly speaking, the exponential of the underlying technology has gone about as

I expected it to go. There's plus or minus

a year or two here and there. I don't know that I would've

predicted the specific direction of code. But when I look at the exponential,

it is roughly what I expected in terms of the march of the models from smart high

school student to smart college student to beginning to do PhD and professional stuff,

and in the case of code reaching beyond that. The frontier is a little bit uneven, but it's

roughly what I expected. What has been the most surprising

thing is the lack of public recognition of how close we are to the end of the exponential.

To me, it is absolutely wild that you have people — within the bubble and outside the

bubble — talking about the same tired, old hot-button political issues, when we are

near the end of the exponential. I want to understand what that

exponential looks like right now. The first question I asked you when

we recorded three years ago was, "what’s up with scaling and why does it work?"

I have a similar question now, but it feels more complicated.

At least from the public's point of view, three years ago there were well-known public trends

across many orders of magnitude of compute where you could see how the loss improves.

Now we have RL scaling and there's no publicly known scaling law for it.

It's not even clear what the story is. Is this supposed to be teaching the model skills?

Is it supposed to be teaching meta-learning? What is the scaling hypothesis at this point?

I actually have the same hypothesis I had even all the way back in 2017.

I think I talked about it last time, but I wrote a doc called "The Big Blob of Compute Hypothesis".

It wasn't about the scaling of language models in particular.

When I wrote it GPT-1 had just come out. That was one among many things.

Back in those days there was robotics. People tried to work on reasoning as

a separate thing from language models, and there was scaling of the kind of RL

that happened in AlphaGo and in Dota at OpenAI. People remember StarCraft at DeepMind, AlphaStar.

It was written as a more general document. Rich Sutton put out "The Bitter

Lesson" a couple years later. The hypothesis is basically the same.

What it says is that all the cleverness, all the techniques, all the "we need a new method to do

something", that doesn't matter very much. There are only a few things that matter.

I think I listed seven of them. One is how much raw compute you have.

The second is the quantity of data. The third is the quality and distribution of data.

It needs to be a broad distribution. The fourth is how long you train for.

The fifth is that you need an objective function that can scale to the moon.

The pre-training objective function is one such objective function.

Another is the RL objective function that says you have a goal,

you're going to go out and reach the goal. Within that, there's objective rewards like

you see in math and coding, and there's more subjective rewards like you see in

RLHF or higher-order versions of that. Then the sixth and seventh were things

around normalization or conditioning, just getting the numerical stability

so that the big blob of compute flows in this laminar way instead of running into problems.

That was the hypothesis, and it's a hypothesis I still hold.

I don't think I've seen very much that is not in line with it.

The pre-training scaling laws were one example of what we see there. Those have continued going.

Now it's been widely reported, we feel good about pre-training.

It’s continuing to give us gains. What has changed is that now we're

also seeing the same thing for RL. We're seeing a pre-training phase

and then an RL phase on top of that. With RL, it’s actually just the same.

Even other companies have published things in some of their releases that say, "We train the

model on math contests — AIME or other things — and how well the model does is log-linear in

how long we've trained it." We see that as well,

and it's not just math contests. It's a wide variety of RL tasks.

We're seeing the same scaling in RL that we saw for pre-training.

You mentioned Rich Sutton and "The Bitter Lesson". I interviewed him last year,

and he's actually very non-LLM-pilled. I don’t know if this is his perspective,

but one way to paraphrase his objection is: Something which possesses the true core of human

learning would not require all these billions of dollars of data and compute and these bespoke

environments, to learn how to use Excel, how to use PowerPoint, how to navigate a web browser.

The fact that we have to build in these skills using these RL environments hints that we are

actually lacking a core human learning algorithm. So we're scaling the wrong thing. That does raise

the question. Why are we doing all this RL scaling if we think there's something that's going to be

human-like in its ability to learn on the fly? I think this puts together several things that

should be thought of differently. There is a genuine puzzle here,

but it may not matter. In fact, I would guess it probably

doesn't matter. There is an interesting thing. Let me take the RL out of it for a second, because I

actually think it's a red herring to say that RL is any different from pre-training in this matter.

If we look at pre-training scaling, it was very interesting

back in 2017 when Alec Radford was doing GPT-1. The models before GPT-1 were trained on datasets

that didn't represent a wide distribution of text. You had very standard language

modeling benchmarks. GPT-1 itself was trained on

a bunch of fanfiction, I think actually. It was literary text, which is a very

small fraction of the text you can get. In those days it was like a billion words

or something, so small datasets representing a pretty narrow distribution of what you can

see in the world. It didn't generalize well. If you did better on some fanfiction corpus,

it wouldn't generalize that well to other tasks. We had all these measures. We had

all these measures of how well it did at predicting all these other kinds of texts.

It was only when you trained over all the tasks on the internet — when you did a general internet

scrape from something like Common Crawl or scraping links in Reddit, which is what we did for

GPT-2 — that you started to get generalization. I think we're seeing the same thing on RL.

We're starting first with simple RL tasks like training on math competitions, then moving to

broader training that involves things like code. Now we're moving to many other tasks.

I think then we're going to increasingly get generalization.

So that kind of takes out the RL vs. pre-training side of it.

But there is a puzzle either way, which is that in pre-training we use trillions of tokens.

Humans don't see trillions of words. So there is an actual sample

efficiency difference here. There is actually something different here.

The models start from scratch and they need much more training.

But we also see that once they're trained, if we give them a long context length of

a million — the only thing blocking long context is inference — they're very good at

learning and adapting within that context. So I don’t know the full answer to this.

I think there's something going on where pre-training is not like

the process of humans learning, but it's somewhere between the process of humans

learning and the process of human evolution. We get many of our priors from evolution.

Our brain isn't just a blank slate. Whole books have been written about this.

The language models are much more like blank slates.

They literally start as random weights, whereas the human brain starts with all these regions

connected to all these inputs and outputs. Maybe we should think of pre-training — and

for that matter, RL as well — as something that exists in the middle space between

human evolution and human on-the-spot learning. And we should think of the in-context learning

that the models do as something between long-term human learning and short-term human learning.

So there's this hierarchy. There’s evolution, there's long-term learning, there's short-term

learning, and there's just human reaction. The LLM phases exist along this spectrum,

but not necessarily at exactly the same points. There’s no analog to some of the human modes

of learning the LLMs are falling in between the points. Does that make sense?

Yes, although some things are still a bit confusing.

For example, if the analogy is that this is like evolution so it's fine that it's

not sample efficient, then if we're going to get super sample-efficient

agent from in-context learning, why are we bothering to build all these RL environments?

There are companies whose work seems to be teaching models how to use this API,

how to use Slack, how to use whatever. It's confusing to me why there's so much emphasis

on that if the kind of agent that can just learn on the fly is emerging or has already emerged.

I can't speak for the emphasis of anyone else. I can only talk about how we think about it.

The goal is not to teach the model every possible skill within RL,

just as we don't do that within pre-training. Within pre-training, we're not trying to expose

the model to every possible way that words could be put together.

Rather, the model trains on a lot of things and then reaches generalization across pre-training.

That was the transition from GPT-1 to GPT-2 that I saw up close. The model reaches a point. I had

these moments where I was like, "Oh yeah, you just give the model a list of numbers — this is

the cost of the house, this is the square feet of the house — and the model completes the pattern

and does linear regression." Not great, but it does it,

and it's never seen that exact thing before. So to the extent that we are building these

RL environments, the goal is very similar to what was done five or ten years ago with pre-training.

We're trying to get a whole bunch of data, not because we want to cover a specific document or a

specific skill, but because we want to generalize. I think the framework you're laying down obviously

makes sense. We're making progress toward AGI. Nobody at this point disagrees we're going to

achieve AGI this century. The crux is you say we're

hitting the end of the exponential. Somebody else looks at this and says,

"We've been making progress since 2012, and by 2035 we'll have a human-like agent."

Obviously we’re seeing in these models the kinds of things that evolution did,

or that learning within a human lifetime does. I want to understand what you’re seeing

that makes you think it's one year away and not ten years away.

There are two claims you could make here, one stronger and one weaker.

Starting with the weaker claim, when I first saw the scaling back in 2019,

I wasn’t sure. This was a 50/50 thing. I thought I saw something. My claim was that this

was much more likely than anyone thinks. Maybe there's a 50% chance this happens.

On the basic hypothesis of, as you put it, within ten years we'll get to what I call a "country of

geniuses in a data center", I'm at 90% on that. It's hard to go much higher than 90%

because the world is so unpredictable. Maybe the irreducible uncertainty puts us at 95%,

where you get to things like multiple companies having internal turmoil, Taiwan gets invaded,

all the fabs get blown up by missiles. Now you've jinxed us, Dario.

You could construct a 5% world where things get delayed for ten years.

There's another 5% which is that I'm very confident on tasks that can be verified.

With coding, except for that irreducible uncertainty,

I think we'll be there in one or two years. There's no way we will not be there in ten years

in terms of being able to do end-to-end coding. My one little bit of fundamental uncertainty,

even on long timescales, is about tasks that aren't verifiable: planning a mission to Mars;

doing some fundamental scientific discovery like CRISPR; writing a novel.

It’s hard to verify those tasks. I am almost certain we have a

reliable path to get there, but if there's a little bit of uncertainty it's there.

On the ten-year timeline I'm at 90%, which is about as certain as you can be.

I think it's crazy to say that this won't happen by 2035.

In some sane world, it would be outside the mainstream.

But the emphasis on verification hints to me a lack of belief that these models are generalized.

If you think about humans, we're both good at things for which we get verifiable reward

and things for which we don't. No, this is why I’m almost sure.

We already see substantial generalization from things that verify to things that

don't. We're already seeing that. But it seems like you were emphasizing

this as a spectrum which will split apart which domains in which we see more progress.

That doesn't seem like how humans get better. The world in which we don't get there is the world

in which we do all the verifiable things. Many of them generalize,

but we don't fully get there. We don’t fully color in the other side

of the box. It's not a binary thing. Even if generalization is weak and you can only do

verifiable domains, it's not clear to me you could automate software engineering in such a world.

You are "a software engineer" in some sense, but part of being a software engineer for you involves

writing long memos about your grand vision. I don’t think that’s part of the job of SWE.

That's part of the job of the company, not SWE specifically.

But SWE does involve design documents and other things like that.

The models are already pretty good at writing comments.

Again, I’m making much weaker claims here than I believe, to distinguish between two things.

We're already almost there for software engineering.

By what metric? There's one metric which is how many lines of code are written by AI.

If you consider other productivity improvements in the history of software engineering,

compilers write all the lines of software. There's a difference between how many lines

are written and how big the productivity improvement is. "We’re almost there" meaning…

How big is the productivity improvement, not just how many lines are written by AI?

I actually agree with you on this. I've made a series of predictions on

code and software engineering. I think people have repeatedly misunderstood them.

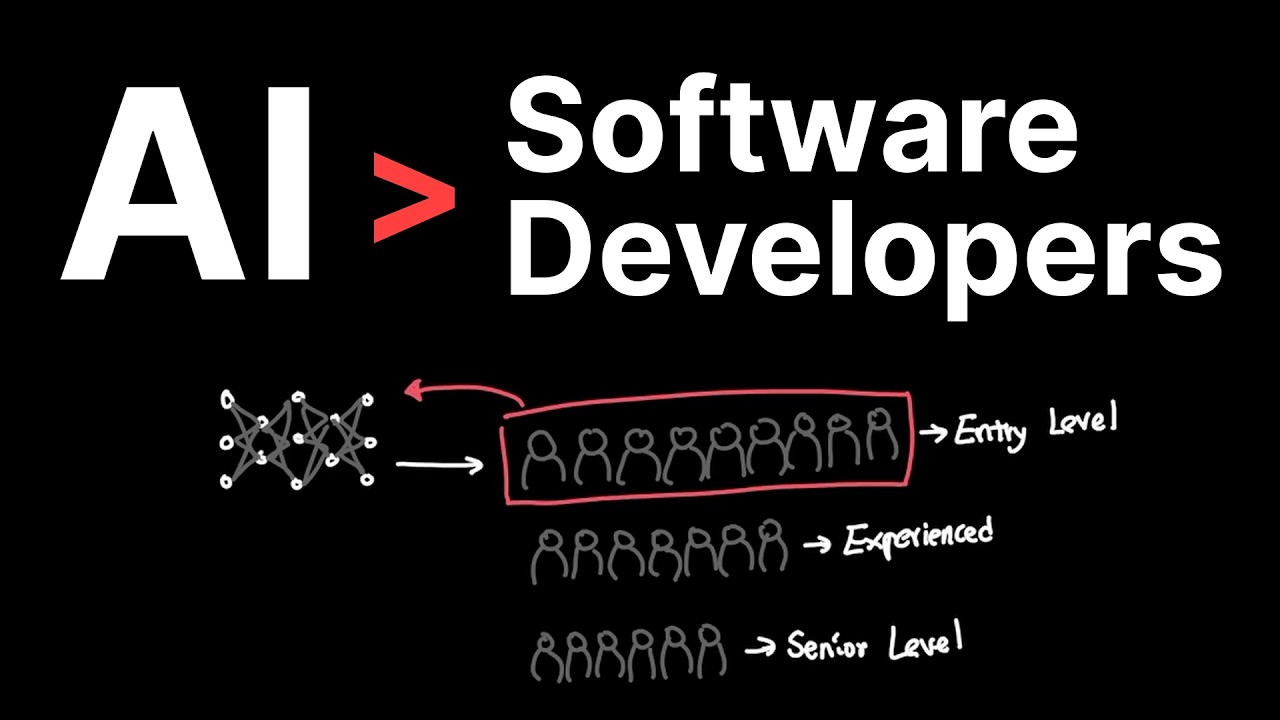

Let me lay out the spectrum. About eight or nine months ago,

I said the AI model will be writing 90% of the lines of code in three to six months.

That happened, at least at some places. It happened at Anthropic, happened with

many people downstream using our models. But that's actually a very weak criterion.

People thought I was saying that we won't need 90% of the software engineers. Those things are worlds

apart. The spectrum is: 90% of code is written by the model, 100% of code is written by the model.

That's a big difference in productivity. 90% of the end-to-end SWE tasks — including

things like compiling, setting up clusters and environments, testing features,

writing memos — are done by the models. 100% of today's SWE tasks are done by the models.

Even when that happens, it doesn't mean software engineers are out of a job.

There are new higher-level things they can do, where they can manage.

Then further down the spectrum, there's 90% less demand for SWEs, which I think

will happen but this is a spectrum. I wrote about it in "The Adolescence

of Technology" where I went through this kind of spectrum with farming.

I actually totally agree with you on that.

These are very different benchmarks from each other,

but we're proceeding through them super fast. Part of your vision is that going from 90 to 100

is going to happen fast, and that it leads to huge productivity improvements.

But what I notice is that even in greenfield projects people start with Claude Code or

something, people report starting a lot of projects… Do we see in the world out there

a renaissance of software, all these new features that wouldn't exist otherwise?

At least so far, it doesn't seem like we see that. So that does make me wonder.

Even if I never had to intervene with Claude Code, the world is complicated.

Jobs are complicated. Closing the loop on self-contained systems, whether it’s just

writing software or something, how much broader gains would we see just from that?

Maybe that should dilute our estimation of the "country of geniuses".

I simultaneously agree with you that it's a reason why these things don't happen instantly,

but at the same time, I think the effect is gonna be very fast.

You could have these two poles. One is that AI is not going to make

progress. It's slow. It's going to take forever to diffuse within the economy.

Economic diffusion has become one of these buzzwords that's a reason why

we're not going to make AI progress, or why AI progress doesn't matter.

The other axis is that we'll get recursive self-improvement, the whole thing.

Can't you just draw an exponential line on the curve?

We're going to have Dyson spheres around the sun so many nanoseconds after we get recursive.

I'm completely caricaturing the view here, but there are these two extremes.

But what we've seen from the beginning, at least if you look within Anthropic, there's this bizarre

10x per year growth in revenue that we've seen. So in 2023, it was zero to $100 million.

In 2024, it was $100 million to $1 billion. In 2025, it was $1 billion to $ 9-10 billion.

You guys should have just bought a billion dollars of your own products so you could just…

And the first month of this year, that exponential is...

You would think it would slow down, but we added another few billion to revenue in January.

Obviously that curve can't go on forever. The GDP is only so large.

I would even guess that it bends somewhat this year, but that is a fast curve. That's a really

fast curve. I would bet it stays pretty fast even as the scale goes to the entire economy.

So I think we should be thinking about this middle world where things are extremely fast, but not

instant, where they take time because of economic diffusion, because of the need to close the loop.

Because it's fiddly: "I have to do change management within my enterprise… I set this up,

but I have to change the security permissions on this in order to make it actually work…

I had this old piece of software that checks the model before it's compiled

and released and I have to rewrite it. Yes, the model can do that, but I have

to tell the model to do that. It has to take time to do that."

So I think everything we've seen so far is compatible with the idea that there's one fast

exponential that's the capability of the model. Then there's another fast exponential

that's downstream of that, which is the diffusion of the model into the economy.

Not instant, not slow, much faster than any previous technology, but it has its limits.

When I look inside Anthropic, when I look at our customers: fast adoption, but not infinitely fast.

Can I try a hot take on you? Yeah.

I feel like diffusion is cope that people say. When the model isn't able to do something,

they're like, "oh, but it's a diffusion issue." But then you should use the comparison to humans.

You would think that the inherent advantages that AIs have would make diffusion a much easier

problem for new AIs getting onboarded than new humans getting onboarded.

An AI can read your entire Slack and your drive in minutes.

They can share all the knowledge that the other copies of the same instance have.

You don't have this adverse selection problem when you're hiring AI, so you

can just hire copies of a vetted AI model. Hiring a human is so much more of a hassle.

People hire humans all the time. We pay humans upwards of $50 trillion

in wages because they're useful, even though in principle it would be much easier to integrate

AIs into the economy than it is to hire humans. The diffusion doesn't really explain.

I think diffusion is very real and doesn't exclusively have

to do with limitations on the AI models. Again, there are people who use diffusion

as kind of a buzzword to say this isn't a big deal. I'm not talking about that. I'm

not talking about how AI will diffuse at the speed of previous technologies.

I think AI will diffuse much faster than previous technologies have, but not infinitely fast.

I'll just give an example of this. There's Claude Code. Claude Code is extremely easy to set up.

If you're a developer, you can just start using Claude Code.

There is no reason why a developer at a large enterprise should not be adopting

Claude Code as quickly as an individual developer or developer at a startup.

We do everything we can to promote it. We sell Claude Code to enterprises.

Big enterprises, big financial companies, big pharmaceutical companies, all of them are adopting

Claude Code much faster than enterprises typically adopt new technology. But again,

it takes time. Any given feature or any given product, like Claude Code or Cowork, will get

adopted by the individual developers who are on Twitter all the time, by the Series A startups,

many months faster than they will get adopted by a large enterprise that does food sales.

There are just a number of factors. You have to go through legal,

you have to provision it for everyone. It has to pass security and compliance.

The leaders of the company who are further away from the AI revolution are forward-looking,

but they have to say, "Oh, it makes sense for us to spend 50 million.

This is what this Claude Code thing is. This is why it helps our company.

This is why it makes us more productive." Then they have to explain

to the people two levels below. They have to say, "Okay, we have 3,000 developers.

Here's how we're going to roll it out to our developers."

We have conversations like this every day. We are doing everything we can to make

Anthropic's revenue grow 20 or 30x a year instead of 10x a year.

Again, many enterprises are just saying, "This is so productive.

We're going to take shortcuts in our usual procurement process."

They're moving much faster than when we tried to sell them just

the ordinary API, which many of them use. Claude Code is a more compelling product,

but it's not an infinitely compelling product. I don't think even AGI or powerful AI or

"country of geniuses in a data center" will be an infinitely compelling product.

It will be a compelling product enough maybe to get 3-5x, or 10x, a year of growth, even when

you're in the hundreds of billions of dollars, which is extremely hard to do and has never been

done in history before, but not infinitely fast. I buy that it would be a slight slowdown.

Maybe this is not your claim, but sometimes people talk about this like,

"Oh, the capabilities are there, but because of diffusion... otherwise we're basically at AGI".

I don't believe we're basically at AGI. I think if you had the "country

of geniuses in a data center"... If we had the "country of geniuses

in a data center", we would know it. We would know it if you had the

"country of geniuses in a data center". Everyone in this room would know it.

Everyone in Washington would know it. People in rural parts might not know it,

but we would know it. We don't have that now. That is very clear.

Coming back to concrete prediction… Because there are so many different things to disambiguate,

it can be easy to talk past each other when we're talking about capabilities.

For example, when I interviewed you three years ago, I asked you a prediction about what

we should expect three years from now. You were right. You said, "We should expect systems which,

if you talk to them for the course of an hour, it's hard to tell them apart from

a generally well-educated human." I think you were right about that.

I think spiritually I feel unsatisfied because my internal expectation was that such a system could

automate large parts of white-collar work. So it might be more productive to talk about

the actual end capabilities you want from such a system.

I will basically tell you where I think we are. Let me ask a very specific question so that

we can figure out exactly what kinds of capabilities we should think about soon.

Maybe I'll ask about it in the context of a job I understand well, not because it's the most

relevant job, but just because I can evaluate the claims about it. Take video editors. I have

video editors. Part of their job involves learning about our audience's preferences,

learning about my preferences and tastes, and the different trade-offs we have.

They’re, over the course of many months, building up this understanding of context.

The skill and ability they have six months into the job, a model that can

pick up that skill on the job on the fly, when should we expect such an AI system?

I guess what you're talking about is that we're doing this interview for three hours.

Someone's going to come in, someone's going to edit it.

They're going to be like, "Oh, I don't know, Dario scratched his head and we could edit that out."

"Magnify that." "There was this long

discussion that is less interesting to people. There's another thing that's more interesting

to people, so let's make this edit." I think the "country of geniuses in

a data center" will be able to do that. The way it will be able to do that is it will

have general control of a computer screen. You'll be able to feed this in.

It'll be able to also use the computer screen to go on the web, look at all your previous

interviews, look at what people are saying on Twitter in response to your interviews,

talk to you, ask you questions, talk to your staff, look at the history of edits

that you did, and from that, do the job. I think that's dependent on several things.

I think this is one of the things that's actually blocking deployment:

getting to the point on computer use where the models are really masters at using the computer.

We've seen this climb in benchmarks, and benchmarks are always imperfect measures.

But I think when we first released computer use a year and a quarter ago, OSWorld was at maybe 15%.

I don't remember exactly, but we've climbed from that to 65-70%.

There may be harder measures as well, but I think computer use has to pass a point of reliability.

Can I just follow up on that before you move on to the next point?

For years, I've been trying to build different internal LLM tools for myself.

Often I have these text-in, text-out tasks, which should be dead center

in the repertoire of these models. Yet I still hire humans to do them.

If it's something like, "identify what the best clips would be in this transcript",

maybe the LLMs do a seven-out-of-ten job on them. But there's not this ongoing way I can engage

with them to help them get better at the job the way I could with a human employee.

That missing ability, even if you solve computer use, would still block

my ability to offload an actual job to them. This gets back to what we were talking about

before with learning on the job. It's very interesting. I think with the coding agents,

I don't think people would say that learning on the job is what is preventing the coding agents

from doing everything end to end. They keep getting better. We have engineers

at Anthropic who don't write any code. When I look at the productivity, to your

previous question, we have folks who say, "This GPU kernel, this chip, I used to write it myself.

I just have Claude do it." There's this enormous improvement in productivity.

When I see Claude Code, familiarity with the codebase or a feeling that the model

hasn't worked at the company for a year, that's not high up on the list of complaints I see.

I think what I'm saying is that we're kind of taking a different path.

Don't you think with coding that's because there

is an external scaffold of memory which exists instantiated in the codebase?

I don't know how many other jobs have that. Coding made fast progress precisely because

it has this unique advantage that other economic activity doesn't.

But when you say that, what you're implying is that by reading the codebase into the context,

I have everything that the human needed to learn on the job.

So that would be an example of—whether it's written or not, whether it's available or

not—a case where everything you needed to know you got from the context window.

What we think of as learning—"I started this job, it's going to take me six months to understand the

code base"—the model just did it in the context. I honestly don't know how to think about

this because there are people who qualitatively report what you're saying.

I'm sure you saw last year, there was a major study where they had experienced developers try

to close pull requests in repositories that they were familiar with. Those developers reported an

uplift. They reported that they felt more productive with the use of these models.

But in fact, if you look at their output and how much was actually merged back in,

there was a 20% downlift. They were less productive

as a result of using these models. So I'm trying to square the qualitative

feeling that people feel with these models versus, 1) in a macro level,

where is this renaissance of software? And then 2) when people do these independent

evaluations, why are we not seeing the productivity benefits we would expect?

Within Anthropic, this is just really unambiguous. We're under an incredible amount of commercial

pressure and make it even harder for ourselves because we have all this safety stuff we do that

I think we do more than other companies. The pressure to survive economically

while also keeping our values is just incredible. We're trying to keep this 10x revenue curve going.

There is zero time for bullshit. There is zero time for feeling

like we're productive when we're not. These tools make us a lot more productive.

Why do you think we're concerned about competitors using the tools?

Because we think we're ahead of the competitors. We wouldn't be going through all this trouble if

this were secretly reducing our productivity. We see the end productivity every few

months in the form of model launches. There's no kidding yourself about this.

The models make you more productive. 1) People feeling like they're productive is

qualitatively predicted by studies like this. But 2) if I just look at the end output,

obviously you guys are making fast progress. But the idea was supposed to be that with

recursive self-improvement, you make a better AI, the AI helps you build a

better next AI, et cetera, et cetera. What I see instead—if I look at you,

OpenAI, DeepMind—is that people are just shifting around the podium every few months.

Maybe you think that stops because you've won or whatever.

But why are we not seeing the person with the best coding model have this lasting

advantage if in fact there are these enormous productivity gains from the last coding model.

I think my model of the situation is that there's an advantage that's gradually growing.

I would say right now the coding models give maybe, I don't know,

a 15-20% total factor speed up. That's my view. Six months ago, it was maybe 5%.

So it didn't matter. 5% doesn't register. It's now just getting to the point where it's

one of several factors that kind of matters. That's going to keep speeding up.

I think six months ago, there were several companies that were at roughly the same

point because this wasn't a notable factor, but I think it's starting to speed up more and more.

I would also say there are multiple companies that write models that are used for code and we're not

perfectly good at preventing some of these other companies from using our models internally.

So I think everything we're seeing is consistent with this kind of snowball model.

Again, my theme in all of this is all of this is soft takeoff, soft, smooth exponentials,

although the exponentials are relatively steep. So we're seeing this snowball gather momentum

where it's like 10%, 20%, 25%, 40%. As you go, Amdahl's law, you have

to get all the things that are preventing you from closing the loop out of the way.

But this is one of the biggest priorities within Anthropic.

Stepping back, before in the stack we were talking about when do we get this on-the-job learning?

It seems like the point you were making on the coding thing is that we actually

don't need on-the-job learning. You can have tremendous productivity

improvements, you can have potentially trillions of dollars of revenue for AI companies, without

this basic human ability to learn on the job. Maybe that's not your claim, you should clarify.

But in most domains of economic activity, people say, "I hired somebody, they weren't that useful

for the first few months, and then over time they built up the context, understanding."

It's actually hard to define what we're talking about here.

But they got something and then now they're a powerhorse and they're so valuable to us.

If AI doesn't develop this ability to learn on the fly, I'm a bit skeptical that we're going to see

huge changes to the world without that ability. I think two things here. There's the state

of the technology right now. Again, we have these two stages.

We have the pre-training and RL stage where you throw a bunch of data and tasks into

the models and then they generalize. So it's like learning, but it's like

learning from more data and not learning over one human or one model's lifetime.

So again, this is situated between evolution and human learning.

But once you learn all those skills, you have them.

Just like with pre-training, just how the models know more, if I look at a pre-trained model,

it knows more about the history of samurai in Japan than I do.

It knows more about baseball than I do. It knows more about low-pass filters

and electronics, all of these things. Its knowledge is way broader than mine.

So I think even just that may get us to the point where the models are better at everything.

We also have, again, just with scaling the kind of existing setup, the in-context learning.

I would describe it as kind of like human on-the-job learning,

but a little weaker and a little short term. You look at in-context learning and if you give

the model a bunch of examples it does get it. There's real learning that happens in context.

A million tokens is a lot. That can be days of human learning.

If you think about the model reading a million words, how long would it

take me to read a million? Days or weeks at least. So you have these two things.

I think these two things within the existing paradigm may just be enough to get you the

"country of geniuses in a data center". I don't know for sure, but I think

they're going to get you a large fraction of it. There may be gaps, but I certainly think that just

as things are, this is enough to generate trillions of dollars of revenue. That's one. Two,

is this idea of continual learning, this idea of a single model learning on the job.

I think we're working on that too. There's a good chance that in the next

year or two, we also solve that. Again, I think you get most

of the way there without it. The trillions of dollars a year market,

maybe all of the national security implications and the safety implications that I wrote about in

"Adolescence of Technology" can happen without it. But we, and I imagine others, are working on it.

There's a good chance that we will get there within the next year or two.

There are a bunch of ideas. I won't go into all of them in detail, but

one is just to make the context longer. There's nothing preventing

longer contexts from working. You just have to train at longer contexts

and then learn to serve them at inference. Both of those are engineering problems that

we are working on and I would assume others are working on them as well.

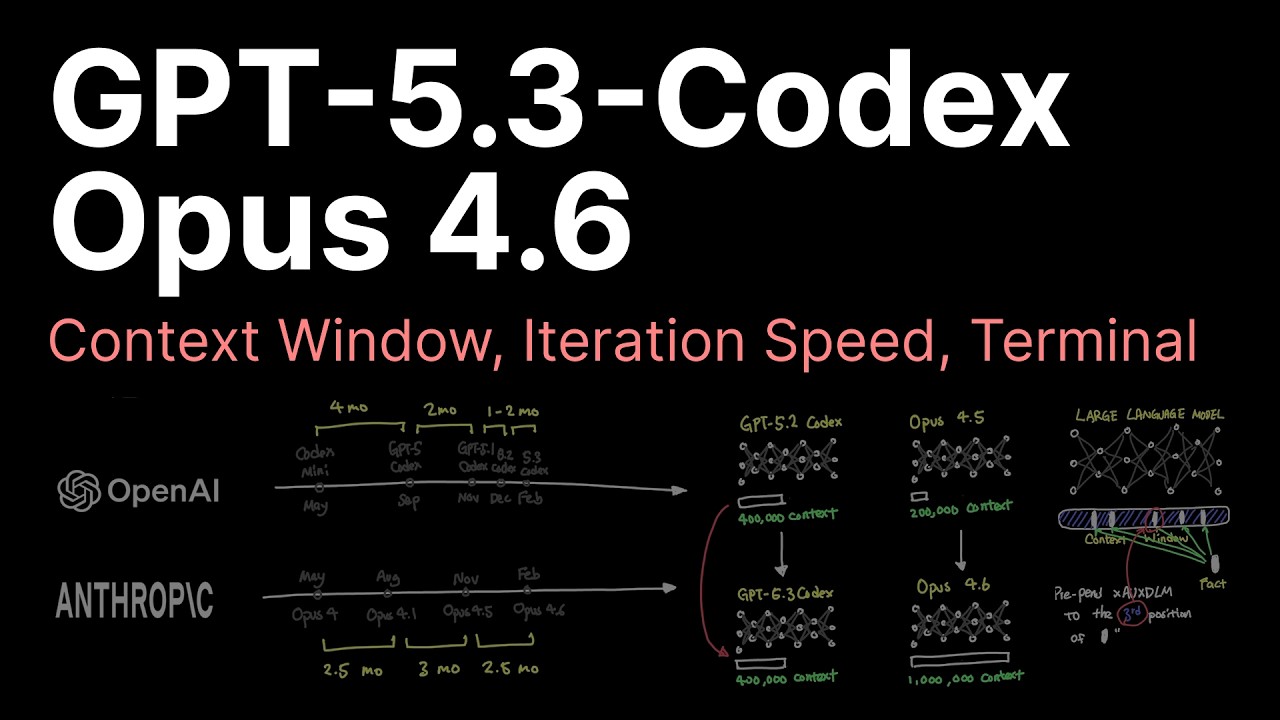

This context length increase, it seemed like there was a period from 2020 to 2023

where from GPT-3 to GPT-4 Turbo, there was an increase from 2000 context lengths to 128K.

I feel like for the two-ish years since then, we've been in the same-ish ballpark.

When context lengths get much longer than that, people report qualitative

degradation in the ability of the model to consider that full context.

So I'm curious what you're internally seeing that makes you think, "10 million contexts,

100 million contexts to get six months of human learning and building context".

This isn't a research problem. This is an engineering and inference problem.

If you want to serve long context, you have to store your entire KV cache.

It's difficult to store all the memory in the GPUs, to juggle the memory around.

I don't even know the details. At this point, this is at a level of detail

that I'm no longer able to follow, although I knew it in the GPT-3 era. "These are the weights,

these are the activations you have to store…" But these days the whole thing is flipped

because we have MoE models and all of that. Regarding this degradation you're talking about,

without getting too specific, there's two things. There's the context length you train at and

there's a context length that you serve at. If you train at a small context length

and then try to serve at a long context length, maybe you get these degradations.

It's better than nothing, you might still offer it, but you get these degradations.

Maybe it's harder to train at a long context length.

I want to, at the same time, ask about maybe some rabbit holes.

Wouldn't you expect that if you had to train on longer context length,

that would mean that you're able to get less samples in for the same amount of compute?

Maybe it's not worth diving deep on that. I want to get an answer to the

bigger picture question. I don't feel a preference

for a human editor that's been working for me for six months versus an AI that's been

working with me for six months, what year do you predict that that will be the case?

My guess for that is there's a lot of problems where basically we can do this when we have

the "country of geniuses in a data center". My picture for that, if you made me guess, is

one to two years, maybe one to three years. It's really hard to tell. I have a strong view—99%,

95%—that all this will happen in 10 years. I think that's just a super safe bet.

I have a hunch—this is more like a 50/50 thing—that it's going to be more like

one to two, maybe more like one to three. So one to three years. Country of geniuses,

and the slightly less economically valuable task of editing videos.

It seems pretty economically valuable, let me tell you.

It's just there are a lot of use cases like that. There are a lot of similar ones.

So you're predicting that within one to three years.

And then, generally, Anthropic has predicted that by late '26 or early '27 we will have AI systems

that "have the ability to navigate interfaces available to humans doing digital work today,

intellectual capabilities matching or exceeding that of Nobel Prize winners, and the ability to

interface with the physical world". You gave an interview two months ago

with DealBook where you were emphasizing your company's more responsible compute

scaling as compared to your competitors. I'm trying to square these two views.

If you really believe that we're going to have a country of geniuses, you want as

big a data center as you can get. There's no reason to slow down.

The TAM of a Nobel Prize winner, that can actually do everything a Nobel Prize

winner can do, is trillions of dollars. So I'm trying to square this conservatism,

which seems rational if you have more moderate timelines, with your stated views about progress.

It actually all fits together. We go back to this fast, but not infinitely fast, diffusion.

Let's say that we're making progress at this rate. The technology is making progress this fast.

I have very high conviction that we're going to get there within a few years.

I have a hunch that we're going to get there within a year or two.

So there’s a little uncertainty on the technical side, but pretty strong

confidence that it won't be off by much. What I'm less certain about is, again,

the economic diffusion side. I really do believe that we could

have models that are a country of geniuses in the data center in one to two years.

One question is: How many years after that do the trillions in revenue start rolling in?

I don't think it's guaranteed that it's going to be immediate.

It could be one year, it could be two years, I could even stretch it to five

years although I'm skeptical of that. So we have this uncertainty. Even if the technology goes as

fast as I suspect that it will, we don't know exactly how fast it's going to drive revenue.

We know it's coming, but with the way you buy these data centers, if you're off by a couple

years, that can be ruinous. It is just like how I

wrote in "Machines of Loving Grace". I said I think we might get this powerful AI,

this "country of genius in the data center". That description you gave comes

from "Machines of Loving Grace". I said we'll get that in 2026, maybe 2027. Again,

that is my hunch. I wouldn't be surprised if I'm off by a year or two, but that is my hunch.

Let's say that happens. That's the starting gun. How long does it take to cure all the diseases?

That's one of the ways that drives a huge amount of economic value. You cure every disease. There's

a question of how much of that goes to the pharmaceutical company or the AI company,

but there's an enormous consumer surplus because —assuming we can get access for everyone,

which I care about greatly—we cure all of these diseases. How long does it take? You

have to do the biological discovery, you have to manufacture the new drug,

you have to go through the regulatory process. We saw this with vaccines and COVID.

We got the vaccine out to everyone, but it took a year and a half.

My question is: How long does it take to get the cure for everything—which AI is the genius

that can in theory invent—out to everyone? How long from when that AI first exists

in the lab to when diseases have actually been cured for everyone?

We've had a polio vaccine for 50 years. We're still trying to eradicate it in the

most remote corners of Africa. The Gates Foundation is trying

as hard as they can. Others are trying as hard

as they can. But that's difficult. Again, I don't expect most of the economic diffusion

to be as difficult as that. That's the most difficult case. But there's a real dilemma here.

Where I've settled on it is that it will be faster than anything we've seen in the

world, but it still has its limits. So when we go to buying data centers,

again, the curve I'm looking at is: we've had a 10x a year increase every year.

At the beginning of this year, we're looking at $10 billion in annualized revenue.

We have to decide how much compute to buy. It takes a year or two to actually build out

the data centers, to reserve the data center. Basically I'm saying, "In 2027,

how much compute do I get?" I could assume that the

revenue will continue growing 10x a year, so it'll be $100 billion at the end of

2026 and $1 trillion at the end of 2027. Actually it would be $5 trillion dollars

of compute because it would be $1 trillion a year for five years.

I could buy $1 trillion of compute that starts at the end of 2027.

If my revenue is not $1 trillion dollars, if it's even $800 billion, there's no force on earth,

there's no hedge on earth that could stop me from going bankrupt if I buy that much compute.

Even though a part of my brain wonders if it's going to keep growing 10x,

I can't buy $1 trillion a year of compute in 2027. If I'm just off by a year in that rate of growth,

or if the growth rate is 5x a year instead of 10x a year, then you go bankrupt.

So you end up in a world where you're supporting hundreds of billions, not trillions.

You accept some risk that there's so much demand that you can't support the revenue,

and you accept some risk that you got it wrong and it's still slow.

When I talked about behaving responsibly, what I meant actually was not the absolute amount.

I think it is true we're spending somewhat less than some of the other players.

It's actually the other things, like have we been thoughtful about it or are we YOLOing and saying,

"We're going to do $100 billion here or $100 billion there"?

I get the impression that some of the other companies have not written down

the spreadsheet, that they don't really understand the risks they're taking.

They're just doing stuff because it sounds cool. We've thought carefully about it. We're

an enterprise business. Therefore, we can rely more on revenue. It's less fickle than consumer.

We have better margins, which is the buffer between buying too much and buying too little.

I think we bought an amount that allows us to capture pretty strong upside worlds.

It won't capture the full 10x a year. Things would have to go pretty badly for

us to be in financial trouble. So we've thought carefully and

we've made that balance. That's what I mean when

I say that we're being responsible. So it seems like it's possible that we

actually just have different definitions of the "country of a genius in a data center".

Because when I think of actual human geniuses, an actual country of human geniuses in a data center,

I would happily buy $5 trillion worth of compute to run an actual country of

human geniuses in a data center. Let's say JPMorgan or Moderna or

whatever doesn't want to use them. I've got a country of geniuses.

They'll start their own company. If they can't start their own company and they're bottlenecked

by clinical trials… It is worth stating that with clinical trials, most clinical trials fail because

the drug doesn't work. There's not efficacy. I make exactly that point in "Machines of

Loving Grace", I say the clinical trials are going to go much faster

than we're used to, but not infinitely fast. Okay, and then suppose it takes a year for

the clinical trials to work out so that you're getting revenue from that and can make more drugs.

Okay, well, you've got a country of geniuses and you're an AI lab.

You could use many more AI researchers. You also think there are these self-reinforcing

gains from smart people working on AI tech. You can have the data center

working on AI progress. Are there substantially

more gains from buying $1 trillion a year of compute versus $300 billion a year of compute?

If your competitor is buying a trillion, yes there is.

Well, no, there's some gain, but then again, there's this chance that they go bankrupt before.

Again, if you're off by only a year, you destroy yourselves. That's the balance. We're

buying a lot. We're buying a hell of a lot. We're buying an amount that's comparable to

what the biggest players in the game are buying. But if you're asking me, "Why haven't we signed

$10 trillion of compute starting in mid-2027?"... First of all, it can't be produced.

There isn't that much in the world. But second, what if the country of

geniuses comes, but it comes in mid-2028 instead of mid-2027? You go bankrupt.

So if your projection is one to three years, it seems like you should want

$10 trillion of compute by 2029 at the latest? Even in the longest version of the timelines

you state, the compute you are ramping up to build doesn't seem in accordance.

What makes you think that? Human wages, let's say,

are on the order of $50 trillion a year— So I won't talk about Anthropic in particular,

but if you talk about the industry, the amount of compute the industry is building this year is

probably, call it, 10-15 gigawatts. It goes up by roughly 3x a year.

So next year's 30-40 gigawatts. 2028 might be 100 gigawatts. 2029 might be like 300 gigawatts.

I'm doing the math in my head, but each gigawatt costs maybe $10 billion,

on the order of $10-15 billion a year. You put that all together and you're

getting about what you described. You’re getting exactly that. You're getting multiple

trillions a year by 2028 or 2029. You're getting exactly what you predict.

That's for the industry. That's for the industry, that’s right.

Suppose Anthropic's compute keeps 3x-ing a year, and then by 2027-28, you have 10 gigawatts.

Multiply that by, as you say, $10 billion. So then it's like $100 billion a year.

But then you're saying the TAM by 2028 is $200 billion.

Again, I don't want to give exact numbers for Anthropic, but these numbers are too small.

Okay, interesting. You've told investors

that you plan to be profitable starting in 2028. This is the year when we're potentially getting

the country of geniuses as a data center. This is now going to unlock all this progress

in medicine and health and new technologies. Wouldn't this be exactly the time where you'd

want to reinvest in the business and build bigger "countries" so they can make more discoveries?

Profitability is this kind of weird thing in this field.

I don't think in this field profitability is actually a measure of spending down

versus investing in the business. Let's just take a model of this.

I actually think profitability happens when you underestimated the amount of demand you were going

to get and loss happens when you overestimated the amount of demand you were going to get,

because you're buying the data centers ahead of time. Think about it this way. Again,

these are stylized facts. These numbers are not exact. I'm just trying to make a toy model here.

Let's say half of your compute is for training and half of your compute is for inference.

The inference has some gross margin that's more than 50%.

So what that means is that if you were in steady-state, you build a data center and if

you knew exactly the demand you were getting, you would get a certain amount of revenue.

Let’s say you pay $100 billion a year for compute. On $50 billion a year you support

$150 billion of revenue. The other $50 billion is used for training.

Basically you’re profitable and you make $50 billion of profit.

Those are the economics of the industry today, or not today but where we’re

projecting forward in a year or two. The only thing that makes that not the

case is if you get less demand than $50 billion. Then you have more than 50% of your data center

for research and you're not profitable. So you train stronger models,

but you're not profitable. If you get more demand than you thought, then

research gets squeezed, but you're kind of able to support more inference and you're more profitable.

Maybe I'm not explaining it well, but the thing I'm trying to say is that you

decide the amount of compute first. Then you have some target desire of

inference versus training, but that gets determined by demand.

It doesn't get determined by you. What I'm hearing is the reason

you're predicting profit is that you are systematically underinvesting in compute?

No, no, no. I'm saying it's hard to predict. These things about 2028 and when it will happen,

that's our attempt to do the best we can with investors.

All of this stuff is really uncertain because of the cone of uncertainty.

We could be profitable in 2026 if the revenue grows fast enough.

If we overestimate or underestimate the next year, that could swing wildly.

What I'm trying to get at is that you have a model in your head of a business that invests,

invests, invests, gets scale and then becomes profitable.

There's a single point at which things turn around.

I don't think the economics of this industry work that way.

I see. So if I'm understanding correctly, you're saying that because of the discrepancy

between the amount of compute we should have gotten and the amount of compute we got,

we were sort of forced to make profit. But that doesn't mean we're going

to continue making profit. We're going to reinvest the money

because now AI has made so much progress and we want a bigger country of geniuses.

So back into revenue is high, but losses are also high.

If every year we predict exactly what the demand is going to be, we'll be profitable every year.

Because spending 50% of your compute on research, roughly, plus a gross margin that's higher than

50% and correct demand prediction leads to profit. That's the profitable business model that I think

is kind of there, but obscured by these building ahead and prediction errors.

I guess you're treating the 50% as a sort of given constant, whereas in fact,

if AI progress is fast and you can increase the progress by scaling up more, you should just have

more than 50% and not make profit. But here's what I'll say. You

might want to scale it up more. Remember the log returns to scale.

If 70% would get you a very little bit of a smaller model through a factor of 1.4x...

That extra $20 billion, each dollar there is worth much less to you because of the log-linear setup.

So you might find that it's better to invest that $20 billion in serving

inference or in hiring engineers who are kind of better at what they're doing.

So the reason I said 50%... That's not exactly our target. It's not exactly going to be 50%.

It’ll probably vary over time. What I'm saying is the log-linear return, what it leads to is you

spend of order one fraction of the business. Like not 5%, not 95%. Then you get diminishing returns.

I feel strange that I'm convincing Dario to believe in AI progress or something.

Okay, you don't invest in research because it has diminishing returns,

but you invest in the other things you mentioned. I think profit at a sort of macro level—

Again, I'm talking about diminishing returns, but after you're spending $50 billion a year.

This is a point I'm sure you would make, but diminishing returns on a genius could

be quite high. More generally,

what is profit in a market economy? Profit is basically saying other

companies in the market can do more things with this money than I can.

Put aside Anthropic. I don't want to give information about Anthropic.

That’s why I'm giving these stylized numbers. But let's just derive the

equilibrium of the industry. Why doesn't everyone spend 100% of their

compute on training and not serve any customers? It's because if they didn't get any revenue,

they couldn't raise money, they couldn't do compute deals,

they couldn't buy more compute the next year. So there's going to be an equilibrium where every

company spends less than 100% on training and certainly less than 100% on inference.

It should be clear why you don't just serve the current models and never train another model,

because then you don't have any demand because you'll fall behind. So there's some equilibrium.

It's not gonna be 10%, it's not gonna be 90%. Let's just say as a stylized fact, it's 50%.

That's what I'm getting at. I think we're gonna be in a position where that equilibrium of how much

you spend on training is less than the gross margins that you're able to get on compute.

So the underlying economics are profitable. The problem is you have this hellish demand

prediction problem when you're buying the next year of compute and you might guess under and be

very profitable but have no compute for research. Or you might guess over and you are not

profitable and you have all the compute for research in the world. Does that make sense?

Just as a dynamic model of the industry? Maybe stepping back, I'm not saying I think

the "country of geniuses" is going to come in two years and therefore you should buy this compute.

To me, the end conclusion you're arriving at makes a lot of sense.

But that's because it seems like "country of geniuses" is hard and there's a long way to go.

So stepping back, the thing I'm trying to get at is more that it seems like your worldview

is compatible with somebody who says, "We're like 10 years away from a world in which we're

generating trillions of dollars of value." That's just not my view. So I'll make

another prediction. It is hard for me to see that there won't be trillions

of dollars in revenue before 2030. I can construct a plausible world.

It takes maybe three years. That would be the end of what I think it's plausible.

Like in 2028, we get the real "country of geniuses in the data center".

The revenue's going into the low hundreds of billions by 2028, and then the country

of geniuses accelerates it to trillions. We’re basically on the slow end of diffusion.

It takes two years to get to the trillions. That would be the world where it takes until 2030.

I suspect even composing the technical exponential and diffusion exponential,

we’ll get there before 2030. So you laid out a model where Anthropic makes

profit because it seems like fundamentally we're in a compute-constrained world.

So eventually we keep growing compute— I think the way the profit comes is… Again,

let's just abstract the whole industry here. Let's just imagine we're in an economics textbook.

We have a small number of firms. Each can invest a limited amount.

Each can invest some fraction in R&D. They have some marginal cost to serve.

The gross profit margins on that marginal cost are very high because inference is efficient.

There's some competition, but the models are also differentiated.

Companies will compete to push their research budgets up.

But because there's a small number of players, we have the... What is it called?

The Cournot equilibrium, I think, is what the small number of firm equilibrium is.

The point is it doesn't equilibrate to perfect competition with zero margins.

If there's three firms in the economy and all are kind of independently behaving rationally,

it doesn't equilibrate to zero. Help me understand that, because

right now we do have three leading firms and they're not making profit. So what is changing?

Again, the gross margins right now are very positive.

What's happening is a combination of two things. One is that we're still in the exponential

scale-up phase of compute. A model gets trained. Let's say a model got

trained that costs $1 billion last year. Then this year it produced $4 billion of

revenue and cost $1 billion to inference from. Again, I'm using stylized numbers here, but that

would be 75% gross margins and this 25% tax. So that model as a whole makes $2 billion.

But at the same time, we're spending $10 billion to train the next model because

there's an exponential scale-up. So the company loses money. Each model

makes money, but the company loses money. The equilibrium I'm talking about is an

equilibrium where we have the "country of geniuses in a data center", but that

model training scale-up has equilibrated more. Maybe it's still going up. We're still trying to

predict the demand, but it's more leveled out. I'm confused about a couple of things there.

Let's start with the current world. In the current world, you're right that,

as you said before, if you treat each individual model as a company, it's profitable.

But of course, a big part of the production function of being a frontier lab is training

the next model, right? Yes, that's right.

If you didn't do that, then you'd make profit for two months and then

you wouldn't have margins because you wouldn't have the best model.

But at some point that reaches the biggest scale that it can reach.

And then in equilibrium, we have algorithmic improvements, but we're spending roughly the

same amount to train the next model as we spend to train the current model.

At some point you run out of money in the economy. A fixed lump of labor fallacy… The economy is

going to grow, right? That's one of your predictions. We're going

to have the data centers in space. Yes, but this is another example

of the theme I was talking about. The economy will grow much faster

with AI than I think it ever has before. Right now the compute is growing 3x a year.

I don't believe the economy is gonna grow 300% a year.

I said this in "Machines of Loving Grace", I think we may get 10-20%

per year growth in the economy, but we're not gonna get 300% growth in the economy.

So I think in the end, if compute becomes the majority of what the economy produces,

it's gonna be capped by that. So let's assume a model

where compute stays capped. The world where frontier labs are making money

is one where they continue to make fast progress. Because fundamentally your margin is limited by

how good the alternative is. So you are able to make money

because you have a frontier model. If you didn't have a frontier model

you wouldn't be making money. So this model requires there

never to be a steady state. Forever and ever you keep

making more algorithmic progress. I don't think that's true. I mean,

I feel like we're in an economics class. Do you know the Tyler Cowen quote?

We never stop talking about economics. We never stop talking about economics.

So no, I don't think this field's going to be a monopoly.

All my lawyers never want me to say the word "monopoly".

But I don't think this field's going to be a monopoly.

You do get industries in which there are a small number of players.

Not one, but a small number of players. Ordinarily, the way you get monopolies

like Facebook or Meta—I always call them Facebook—is these kinds of network effects.

The way you get industries in which there are a small number of players,

is very high costs of entry. Cloud is like this. I think cloud is a good example of this.

There are three, maybe four, players within cloud. I think that's the same for AI, three, maybe four.

The reason is that it's so expensive. It requires so much expertise and so

much capital to run a cloud company. You have to put up all this capital.

In addition to putting up all this capital, you have to get all of this other stuff

that requires a lot of skill to make it happen. So if you go to someone and you're like, "I want

to disrupt this industry, here's $100 billion." You're like, "okay, I'm putting in $100 billion

and also betting that you can do all these other things that these people have been doing."

Only to decrease the profit. The effect of your entering

is that profit margins go down. So, we have equilibria like this

all the time in the economy where we have a few players. Profits are not astronomical. Margins

are not astronomical, but they're not zero. That's what we see on cloud. Cloud is very

undifferentiated. Models are more differentiated than cloud.

Everyone knows Claude is good at different things than GPT is good at, than Gemini is good at.

It's not just that Claude's good at coding, GPT is good at math and reasoning.

It's more subtle than that. Models are good at different types of coding. Models have different

styles. I think these things are actually quite different from each other, and so I would expect

more differentiation than you see in cloud. Now, there actually is one counter-argument.

That counter-argument is if the process of producing models,

if AI models can do that themselves, then that could spread throughout the economy.

But that is not an argument for commoditizing AI models in general.

That's kind of an argument for commoditizing the whole economy at once.

I don't know what quite happens in that world where basically anyone

can do anything, anyone can build anything, and there's no moat around anything at all.

I don't know, maybe we want that world. Maybe that's the end state here.

Maybe when AI models can do everything, if we've solved all the safety and security problems,

that's one of the mechanisms for the economy just flattening itself again.

But that's kind of far post-"country of geniuses in the data center."

Maybe a finer way to put that potential point is: 1) it seems like AI research is especially

loaded on raw intellectual power, which will be especially abundant in the world of AGI.

And 2) if you just look at the world today, there are very few technologies that seem to be

diffusing as fast as AI algorithmic progress. So that does hint that this industry is

sort of structurally diffusive. I think coding is going fast, but

I think AI research is a superset of coding and there are aspects of it that are not going fast.

But I do think, again, once we get coding, once we get AI models going fast, then that will speed up

the ability of AI models to do everything else. So while coding is going fast now, I think once

the AI models are building the next AI models and building everything else,

the whole economy will kind of go at the same pace. I am worried geographically, though.

I'm a little worried that just proximity to AI, having heard about AI, may be one differentiator.

So when I said the 10-20% growth rate, a worry I have is that the growth rate could be like 50%

in Silicon Valley and parts of the world that are socially connected to Silicon Valley, and not that

much faster than its current pace elsewhere. I think that'd be a pretty messed up world.

So one of the things I think about a lot is how to prevent that.

Do you think that once we have this country of geniuses in a data center, that

robotics is sort of quickly solved afterwards? Because it seems like a big problem with robotics

is that a human can learn how to teleoperate current hardware, but current AI models can't,

at least not in a way that's super productive. And so if we have this ability to learn like

a human, shouldn't it solve robotics immediately as well?

I don't think it's dependent on learning like a human.

It could happen in different ways. Again, we could have trained the model on

many different video games, which are like robotic controls, or many different simulated robotics

environments, or just train them to control computer screens, and they learn to generalize.

So it will happen... it's not necessarily dependent on human-like learning.

Human-like learning is one way it could happen. If the model's like, "Oh, I pick up a robot,

I don't know how to use it, I learn," that could happen because we discovered continual learning.

That could also happen because we trained the model on a bunch of environments and

then generalized, or it could happen because the model learns that in the context length.

It doesn't actually matter which way. If we go back to the discussion we had

an hour ago, that type of thing can happen in several different ways.

But I do think when for whatever reason the models have those skills, then robotics will be

revolutionized—both the design of robots, because the models will be much better than humans at

that, and also the ability to control robots. So we'll get better at building the physical

hardware, building the physical robots, and we'll also get better at controlling it.

Now, does that mean the robotics industry will also be generating

trillions of dollars of revenue? My answer there is yes, but there will be

the same extremely fast, but not infinitely fast diffusion. So will robotics be revolutionized?

Yeah, maybe tack on another year or two. That's the way I think about these things.

Makes sense. There's a general skepticism about extremely fast progress. Here's my view. It sounds

like you are going to solve continual learning one way or another within a matter of years.

But just as people weren't talking about continual learning a couple of years ago,

and then we realized, "Oh, why aren't these models as useful as they could be right now,

even though they are clearly passing the Turing test and are experts in so many different domains?

Maybe it's this thing." Then we solve this thing and we realize, actually, there's another thing

that human intelligence can do that's a basis of human labor that these models can't do.

So why not think there will be more things like this, where

we've found more pieces of human intelligence? Well, to be clear, I think continual learning, as

I've said before, might not be a barrier at all. I think we may just get there by pre-training

generalization and RL generalization. I think there just

might not be such a thing at all. In fact, I would point to the history

in ML of people coming up with things that are barriers that end up kind of

dissolving within the big blob of compute. People talked about, "How do your models

keep track of nouns and verbs?" "They can understand syntactically,

but they can't understand semantically? It's only statistical correlations."

"You can understand a paragraph, you can’t understand a word.

There's reasoning, you can't do reasoning." But then suddenly it turns out you can

do code and math very well. So I think there's actually a

stronger history of some of these things seeming like a big deal and then kind of dissolving. Some

of them are real. The need for data is real, maybe continual learning is a real thing.

But again, I would ground us in something like code.

I think we may get to the point in a year or two where the models can

just do SWE end-to-end. That's a whole task. That's a whole sphere of human activity that

we're just saying models can do now. When you say end-to-end, do you mean

setting technical direction, understanding the context of the problem, et cetera?

Yes. I mean all of that. Interesting. I feel like that is AGI-complete,

which maybe is internally consistent. But it's not like saying 90%

of code or 100% of code. No, I gave this spectrum:

90% of code, 100% of code, 90% of end-to-end SWE, 100% of end-to-end SWE.

New tasks are created for SWEs. Eventually those get done as well.

It's a long spectrum there, but we're traversing the spectrum very quickly.

I do think it's funny that I've seen a couple of podcasts you've done where

the hosts will be like, "But Dwarkesh wrote the essay about the continuous learning thing."

It always makes me crack up because you've been an AI researcher for 10 years.

I'm sure there's some feeling of, "Okay, so a podcaster wrote an essay,

and every interview I get asked about it." The truth of the matter is that we're all

trying to figure this out together. There are some ways in which I'm

able to see things that others aren't. These days that probably has more to do

with seeing a bunch of stuff within Anthropic and having to make a bunch of decisions than I have

any great research insight that others don't. I'm running a 2,500 person company.

It's actually pretty hard for me to have concrete research insight, much harder than it would have

been 10 years ago or even two or three years ago. As we go towards a world of a full drop-in

remote worker replacement, does an API pricing model still make the most sense?

If not, what is the correct way to price AGI, or serve AGI?

I think there's going to be a bunch of different business models here, all at once,

that are going to be experimented with. I actually do think that the API

model is more durable than many people think. One way I think about it is if the technology

is advancing quickly, if it's advancing exponentially, what that means is there's

always a surface area of new use cases that have been developed in the last three months.

Any kind of product surface you put in place is always at risk of sort of becoming irrelevant.

Any given product surface probably makes sense for a range of capabilities of the model.

The chatbot is already running into limitations where making it smarter doesn't really help the

average consumer that much. But I don't think that's

a limitation of AI models. I don't think that's evidence

that the models are good enough and them getting better doesn't matter to the economy.

It doesn't matter to that particular product. So I think the value of the API is that the API

always offers an opportunity, very close to the bare metal, to build on what the latest thing is.

There's always going to be this front of new startups and new ideas that

weren't possible a few months ago and are possible because the model is advancing.

I actually predict that it's going to exist alongside other models, but we're always going

to have the API business model because there's always going to be a need for a thousand different

people to try experimenting with the model in a different way. 100 of them become startups and

ten of them become big successful startups. Two or three really end up being the way

that people use the model of a given generation. So I basically think it's always going to exist.

At the same time, I'm sure there's going to be other models as well.

Not every token that's output by the model is worth the same amount.

Think about what is the value of the tokens that the model outputs when someone calls

them up and says, "My Mac isn't working," or something, the model's like, "restart it."

Someone hasn't heard that before, but the model said that 10 million times.

Maybe that's worth like a dollar or a few cents or something.

Whereas if the model goes to one of the pharmaceutical companies and it says, "Oh,

you know, this molecule you're developing, you should take the aromatic ring from that end of the

molecule and put it on that end of the molecule. If you do that, wonderful things will happen."

Those tokens could be worth tens of millions of dollars.

So I think we're definitely going to see business models that recognize that.

At some point we're going to see "pay for results" in some form, or we may see forms of compensation

that are like labor, that kind of work by the hour. I don't know. I think because it's a new

industry, a lot of things are going to be tried. I don't know what will turn out to

be the right thing. I take your point that

people will have to try things to figure out what is the best way to use this blob of intelligence.

But what I find striking is Claude Code. I don't think in the history of startups

there has been a single application that has been as hotly competed in as coding agents.

Claude Code is a category leader here. That seems surprising to me. It doesn't seem

intrinsically that Anthropic had to build this. I wonder if you have an accounting of why it had

to be Anthropic or how Anthropic ended up building an application in addition

to the model underlying it that was successful. So it actually happened in a pretty simple way,

which is that we had our own coding models, which were good at coding.

Around the beginning of 2025, I said, "I think the time has come where you can have

nontrivial acceleration of your own research if you're an AI company by using these models."

Of course, you need an interface, you need a harness to use them.

So I encouraged people internally. I didn't say this is one thing that you have to use.

I just said people should experiment with this. I think it might have been originally

called Claude CLI, and then the name eventually got changed to Claude Code.